Likelihood Calculations in Diffusion Models

Mr. Fokker and Mr. Planck, meet Ito-San

Let’s start out this blog post with the one equation that is at the heart of diffusion models, the Fokker-Planck equation,

which describes the evolution of the probability density function of a stochastic process that follows a stochastic differential equation

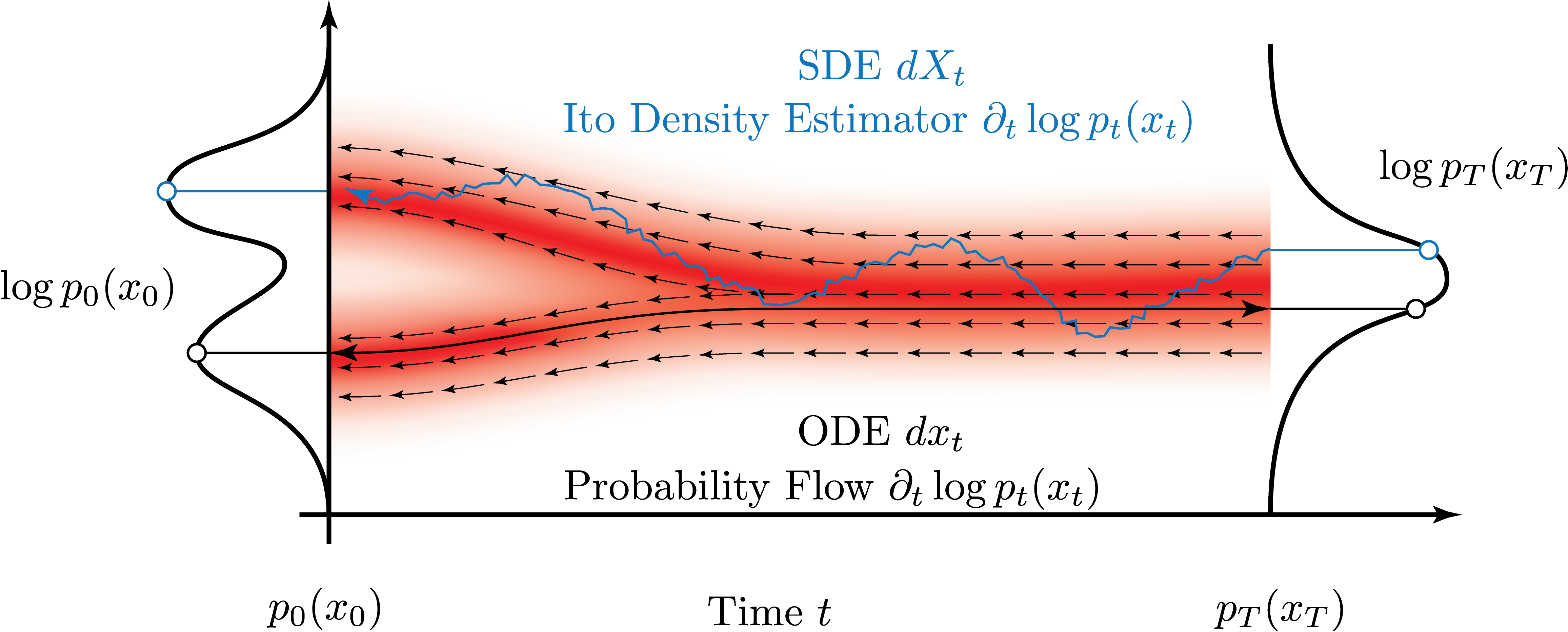

These two equations allow us to work with the underlying stochastic process in two different ways. Either we integrate the stochastic differential equation to obtain the sample path of the process, or we solve the Fokker-Planck equation to obtain the probability density function of the process.

The FPE describes the evolution of the probability density function of a stochastic process. The first term on the right-hand side is the drift term, and the second term is the diffusion term. The drift term is the divergence of the drift vector field $\mathbf{\mu}(x, t)$, and the diffusion term is the Laplacian of the diffusion matrix field $\mathbf{\sigma}(x, t)$. The Fokker-Planck equation is a partial differential equation that describes the evolution of the probability density function of a stochastic process. It is a generalization of the heat equation, which describes the diffusion of heat in a medium.

Following these two ‘representations’ of a stochastic process, we can now ask the question: How can we calculate the likelihood of the observed data given a stochastic process? In the following, we will derive two different ways to calculate the likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model: the probability flow formulation and Ito’s density estimator.

Probability Flows

The first way to compute likelihoods of observed data given a diffusion model is to use the probability flow formulation. This approach rewrites the FPE such that we “pull in” in the diffusive component $\sigma^2(t)$ into the drift component, thereby making the stochastic part “disappear”.

In fact, both the distribution $p(x,t)$ and the sample $x$ are a function of time. To make this really explicit, we can write out the probability distribution as $p(x(t), t)$ and taking its total derivative with respect to time gives us

Essentially, the time $t$ occurs in two places: in the probability distribution $p(x,t)$ and nested in the sample $x(t)$. If we want to derive with respect to the time $t$, we have to consider both the explicit dependence of the probability distribution on the time $p( \cdot , t)$ and the dependence of time in the sample $\partial_t p(x(t), t) = \partial_x p(x(t), t) \ \partial_t x(t)$.

Let’s circle back to the FPE in which we relate the change in time $\partial_t p(x,t)$ to the change in space $\nabla \cdot \mathbf{\mu}(x, t) \ p(x, t)$.

and substituting the FPE into the total derivative yields

Pulling $p(x,t)$ over to the left side then yields the total derivative of the log-likelihood,

The result above is remarkable as it allows us to compute the likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model by integrating an ordinary differential equation. This is in fact a continuous normalizing flow. To apply this way of computing log-likelihoods, we need to identify the deterministic drift, which we saw in equations (5) - (9), and integrate the ODE to obtain the log-likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model.

Computing the log-likelihood of a sample $x(T)$ is then given by integrating the change in the log-likelihood from time $0$ to time $T$:

In code this is comparatively straight forward to compute. The full code can be found in this little repository but we can see the simple OT vector field integration and the likelihood computation below:

for step, t in tqdm(enumerate(torch.linspace(1, 0, n_steps))):

t = t.expand(len(x), 1)

dx = self.forward(t, x)

if likelihood:

likelihood += [likelihood[-1] + divergence(euler_fn, t, x) * dt]

x = x - dx * dt # integrating vector field backwards

# with the divergence code:

def divergence(f, t, x):

"""

Compute the analytical divergence of v(t, x) using PyTorch autograd.

Args:

v_func: Function v(t, x) that computes the velocity field.

x: Input tensor of shape (batch_size, dim).

t: Scalar tensor representing time.

Returns:

Analytical divergence of v(t, x) for each batch element.

"""

batch_size, dim = x.shape

divergence = torch.zeros(batch_size, device=x.device)

with torch.enable_grad():

for i in range(dim):

x.requires_grad_(True)

v_t = f(t, x) # Compute velocity field v(t, x)

grad_outputs = torch.ones_like(

v_t[:, i]

) # Compute gradient wrt each output dimension

div_v_i = torch.autograd.grad(

v_t[:, i],

x,

grad_outputs=grad_outputs,

retain_graph=False,

create_graph=False,

)[0][:, i]

# div_v_i = torch.autograd.grad(v_t[:, i], x, grad_outputs=grad_outputs)[0][:, i]

divergence += div_v_i # Sum over all diagonal elements

x.detach()

x.detach()

return divergence

A small disclaimer: the tricky part is computing the divergence of the drift vector field $\mathbf{\mu}(x, t)$ efficiently. The problem here is that for $D$ dimensions, we have to compute $D$ partial derivatives for each dimension, which can be computationally expensive in higher dimensions. To alleviate this problem, Hutchinson’s stochastic trace estimator is commonly used.

What does the trace have to do with the divergence? Well, essentially the divergence sums over the diagonal elements of the Jacobian matrix $J_\mu \in \mathbb{R}^{D \times D}$ of the drift vector field $\mathbf{\mu}(x, t)$, and $J_{\mu, ij} = \partial_{x_i} \mu_j(x,t)$ by its definition

Hutchinson’s stochastic trace estimator approximates the trace of a matrix by sampling random vectors and computing the inner product of the matrix with the random vectors, like so

Furthemore the term $J_\mu \epsilon$ is a Jacobian-vector product and can be computed efficiently using automatic differentiation.

Effectively, we’re backpropagating the vector $\epsilon$ through the neural network evaluation ( in pseudo-code torch.autograd.grad(outputs=mu, inputs=x, grad_outputs=epsilon)) and contract it with epsilon again.

We do that for multiple samples of $\epsilon$ and average the results to obtain an unbiased estimate of the trace of the Jacobian matrix.

Taking a single sample of $\epsilon$ and computing the Jacobian-vector product is computationally more efficient than computing the full Jacobian matrix but comes with a higher estimator variance.

In code this looks like this:

def stochastic_divergence(f, t, x, num_samples=10):

"""

Compute the divergence of v(t, x) using Hutchinson's trace estimator.

Args:

v_func: Function v(t, x) that computes the velocity field.

x: Input tensor of shape (batch_size, dim).

t: Scalar tensor representing time.

num_samples: Number of Hutchinson samples for estimation.

Returns:

Estimated divergence of v(t, x).

"""

batch_size, dim = x.shape

divergence_estimate = torch.zeros(batch_size, device=x.device)

with torch.enable_grad():

for _ in range(num_samples):

v = torch.randn_like(x) # Sample Gaussian noise v ~ N(0, I)

x.requires_grad_(True) # Enable gradient tracking

v_t = f(t, x) # Compute velocity field v(t, x), shape (batch_size, dim)

div_v = torch.autograd.grad(v_t, x, grad_outputs=v, create_graph=True)[

0

] # Compute Jv

divergence_estimate += torch.sum(div_v * v, dim=1) # Estimate trace

return divergence_estimate / num_samples # Average over samples

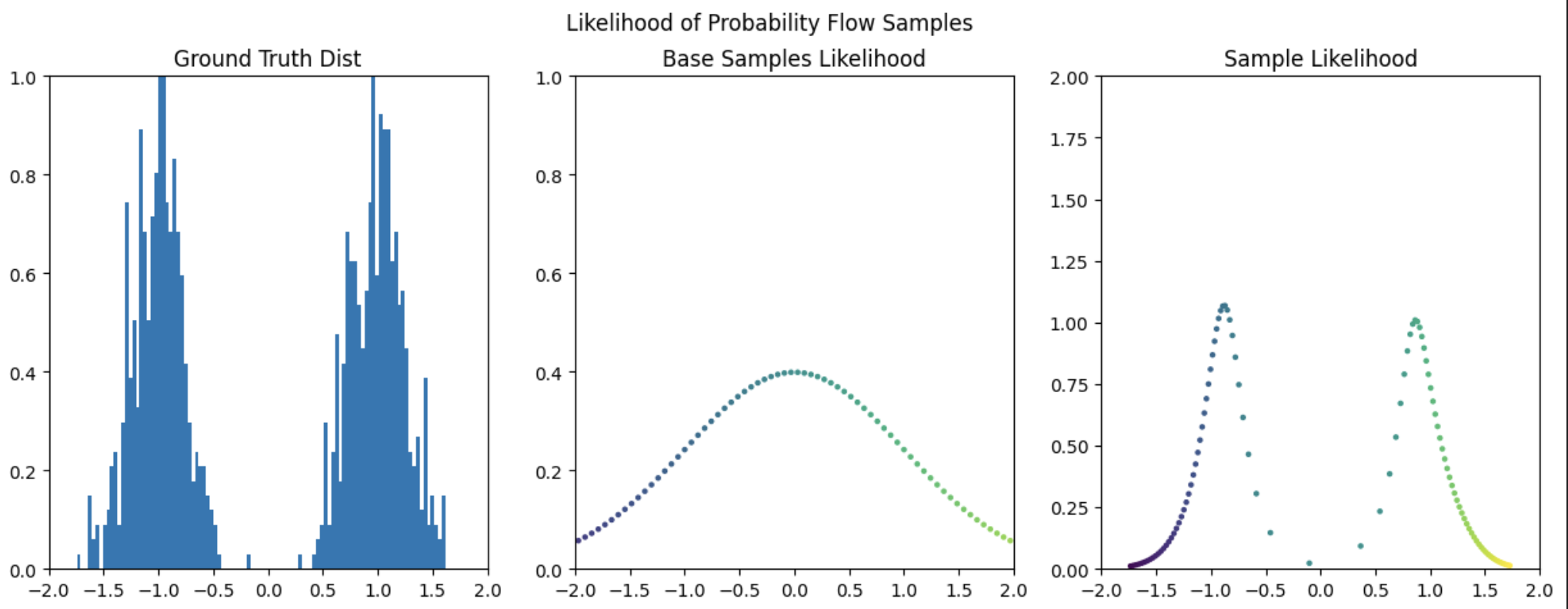

And plotting the corresponding data likelihood for a series of points in the base space yields

Ito Density Estimators

The probability flow log-likelihood estimator is derived through the Fokker-Planck equation. Here we will compute the log-likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model using Ito’s lemma based on the SDE formulation.

We start out by splitting the Laplace operator $\Delta$ into two divergences,

Working with the change in the probability $\partial_t \ p(x,t)$ is nice per se but working with the log-likelihood $\partial_t \ \log p(x,t)$ is even nicer as it is numerically more stable. The goal is therefore to express the change in probability not in the probability space $p(x,t)$ itself but instead in the log-probability space $\log p(x,t)$. To achieve that, we’ll use the chain rule for the log-likelihood which is also known as the log-derivative trick which also applies to the Laplace operator:

The first step is to write out the FPE in terms of the derivatives,

Step two is then to express these derivatives with derivatives of the log-likelihood,

Thus we have obtained an ODE for the log-likelihood (instead of the likelihood $p(x,t)$) for a sample of the diffusion model. This is essentially the log transformed version of the FPE. This equation is actually closely related to the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equation in the context of optimal control theory and was first showcased by Lorenz Richter et al.

This is still a PDE and describes the evolution of the log-probability. But we’re not interested in the overall evolution of the log-probability, but rather in the likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model. Intuitively, we’re only interested in the change of probability of a particular sample $x_t$ which has its own additional dynamics expressed through the sampling SDE.

In order to obtain the total derivative $d \log p(x,t)$ which takes into account the change in probability as well as the change in the sample $x_t$, we have to consider the chain rule for the log-likelihood. For that we will take Ito’s lemma.

For a function function $f(X_t)$ Ito’s lemma calculates the change in the function $df(X_t)$ as a function of the change in the sample $X_t$.

The real application of log-likelihood calculations in diffusion models is to compute the likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model where the flow of time is reversed. To achieve that we ‘simply’ introduce a new time index $\tau = 1 - t$ and respectively $t = 1 - \tau$. Now we can express the time in terms of the reversed time $\tau$,

Applying the time reversion to the log transformed FPE, the evolution of the probability density function in terms of the reversed time $\tau$ is given by:

Now, we’ll hand over the calculations to Ito-san to actually compute the likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model.

The essential step in Skreta et al’s paper is to combine the log-transformed FPE with Ito’s lemma to obtain the likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model. This expresses the total change in log-likelihood originating both from the particle dynamics $dX_t$ and the evolution of the probability density function $d \log p(x_t, t)$.

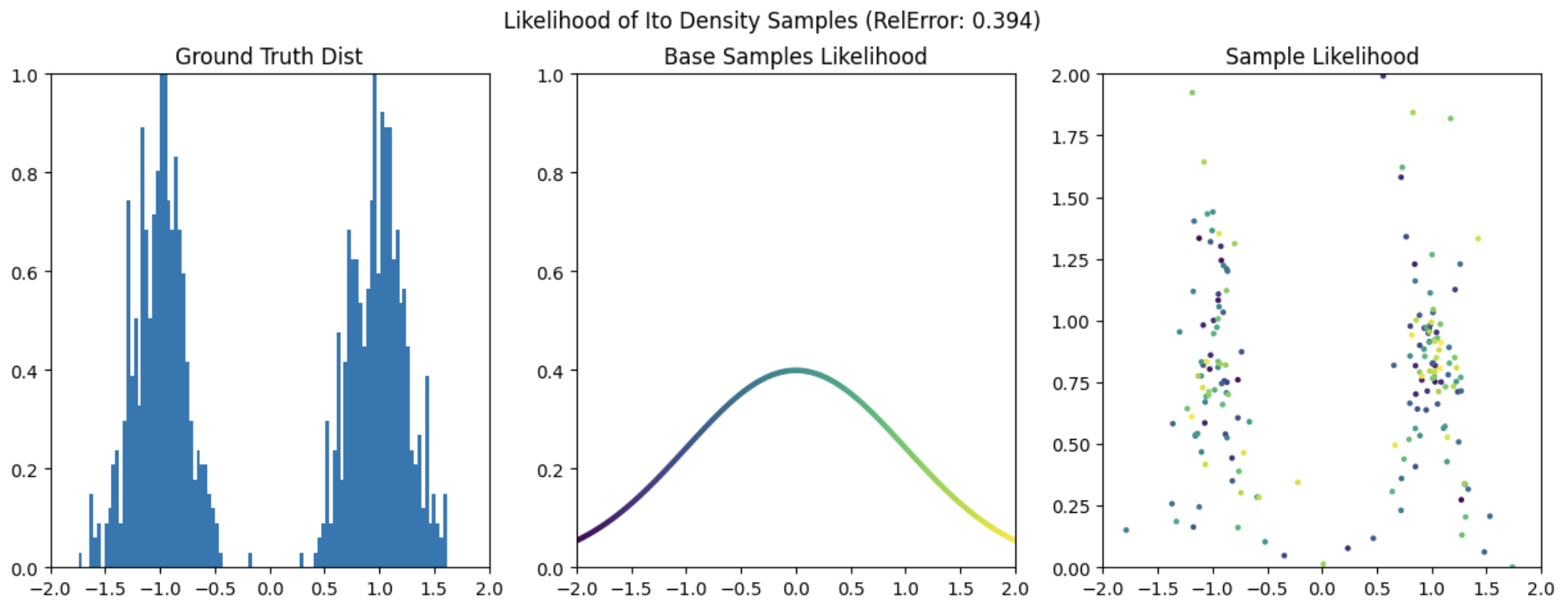

We have

The result above stands in contrast to the probability flow formulation for calculating the likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model. Whereas the probability flow formulation relies on integrating an ODE, here we can directly compute the log-likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model by solving a SDE.

In code this is straight forward to implement like this

for step, t in tqdm(enumerate(torch.linspace(0.99, 0.001, n_steps))):

t = t.expand(len(x), 1)

v = self.forward(t, x)

score = (

1

/ (sigma_t(t) + 1e-6)

* (alpha_t(t) * v - dalpha_t(t) * x)

/ (dalpha_t(t) * sigma_t(t) - alpha_t(t) * dsigma_t(t) + 1e-6)

)

score = score.clamp(-100, 100)

# score = (

# -1 / sigma_t(t) * (x + (1 - t) * v)

# ) # - 1/sigma E[\epsilon | x_t]

drift = f_t(t) * x - 1 / 2 * g_t(t) ** 2 * (1 + diff_t(t) ** 2) * score

brownian_motion = torch.randn_like(x)

diffusion = diff_t(t) * g_t(t) * brownian_motion

x = x + drift * (-dt) + diffusion * dt**0.5

traj.append(x) # x - t * dx for x1 prediction

if likelihood:

# Cartoonist notation: arXiv:2411.01293v2

det_update = -f_t(t) - 1 / 2 * g_t(t) ** 2 * score**2

stoch_update = g_t(t) * score * brownian_motion

update = det_update * (-dt) + stoch_update * dt**0.5

loglikelihood += [loglikelihood[-1] + update.squeeze()]

Transforming Flows to Diffusion Models and back

We saw in the beginning how the probability flow formulation of a SDE can extracted from the corresponding FPE. This is an ordinary differential equation which we can integrate to obtain the log-likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model. The Ito density estimator, on the other hand, is a stochastic differential equation which we can solve to obtain the log-likelihood of the observed data given a diffusion model.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could train a flow with an optimal transport plan, and subsequently transform it into a diffusion model? Can we also transform a diffusion model into a flow?

In order to achieve that should first write out the main equation at the heart of each approach: \(\begin{align} \text{Flow Matching} & \quad : X_t = \alpha_t x_0 + \sigma_t \varepsilon \\ \text{Diffusion Model}& \quad : dX_t = -f_t X_t dt + g_t dW_t \end{align}\)

Ideally we would like to have the integrated diffusion model $\int_0^t dX_t = X_t$ for both the flow matching and the diffusion model. If that were the case, then integrating the diffusion model would yield a random variable witch an identical probability distribution as the flow matching variable $X_t$.

Since integrating stochastic dynamics is always a hassle, we will first look at the average dynamics by taking the expectation over both random variables $dX_t$ and $X_t$. Thus we get \(\begin{align} \text{Flow Matching} & \quad : \mathbb{E}[X_t] = \mathbb{E}[\alpha_t x_0] + \overbrace{\mathbb{E}[\sigma_t \varepsilon]}^{\mathbb{E}[\varepsilon]=0} \\ \text{Diffusion Model}& \quad : \mathbb{E}[dX_t] = \mathbb{E}[-f_t X_t dt] + \underbrace{\mathbb{E}[g_t dW_t]}_{\mathbb{E}[dW_t]=0}. \end{align}\)

Now we want $\mathbb{E}[X_t] = \int_0^t \mathbb{E}[-f_s X_s] ds$ to hold such that we can equate $\alpha_t$ with $\int_0^t -f_s ds$. We proceed by solving the differential equation $dx_t = f_t x_t dt$: \(\begin{align} dx_t &= -f_t x_t dt \\ \frac{dx_t}{x_t} &= -f_t dt \\ d \log x_t &= -f_t dt \\ \int_0^t d\log x_s &= \int_0^t -f_s ds \\ \left[ \log x_s \right]_{s=0}^t &= \int_0^t -f_s ds \\ \log x_t - \log x_0 &= \int_0^t -f_s ds \\ \log \frac{x_t}{x_0} &= \int_0^t -f_s ds \\ x_t &= x_0 \ \exp\left[ \int_0^t -f_s ds\right] \\ &\downarrow \\ \alpha_t &= \exp\left[ \int_0^t -f_s ds \right] \end{align}\)

Comparing that to $x_t = \alpha_t x_0$ we have succesfully identified $\alpha_t = \exp[ \int_0^t -f_s ds]$.

Equating $\sigma_t$ with $g_t$ will be slightly more difficult because we have to factor in the effect of $-f_t X_t$. To properly quantify the relationship between $\sigma_t$ and $g_t$, we would have to first eliminate the effect of the drift. In order to achieve this we can leverage the idea of a martingale which is the fancy word of a SDE without a drift.

For that we define a new stochastic variable $y_t = \frac{x_t}{\alpha_t}$ and differentiating it with either Ito or the quotient rule yields \(\begin{align} dy_t &= d \left[ \frac{x_t}{\alpha_t} \right] \\ &= \frac{dx_t \alpha_t - x_t d\alpha_t}{\alpha_t^2} \\ &= \frac{dx_t}{\alpha_t} - \frac{x_t}{\alpha_t^2} \frac{d\alpha_t}{dt} dt \\ &= \frac{-f_t x_t dt + g_t dW_t}{\alpha_t} - \frac{x_t}{\alpha_t^2} (-f_t) \alpha_t dt \\ &= \cancel{\frac{-f_t x_t dt}{\alpha_t}} + \frac{g_t dW_t}{\alpha_t} - \cancel{\frac{x_t}{\alpha_t} (-f_t) dt} \\ &= \frac{g_t}{\alpha_t} dW_t \end{align}\) yields a SDE without a drift. This implies that the stochastic variable $y_t$ is a martingale where knowing something about the current value $y_t$ does not give us any information about the future value $y_{t+dt}$. This is due to the fact that the drift term is zero and thus this is a scaled Wiener process which could basically go either up or down with equal probability.

This is highly useful as we can now study the diffusion of $y_t$ over time without having to deal with the drift. For martingale, all the convenient properties of Brownian motion hold out of the box, and adding a time-dependent scaling parameter is only a very small nuisance. Integrating this time-dependent Brownian Motion yields \(\begin{align} y_t = y_0 + \int_0^t \frac{g_s}{\alpha_s} dW_s \end{align}\) and pulling the initial condition $y_0$ over to the left side to adjust for the offset of the initial condition we get a variance of \(\begin{align} \mathbb{V}[y_t-y_0] &= \mathbb{E}\left[ ( y_t - y_0 - \mathbb{E}[y_t - y_0])^2 \right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}\left[ \left( \int_0^t \frac{g_s}{\alpha_s} dW_s - \underbrace{\mathbb{E}\left[\int_0^t \frac{g_s}{\alpha_s} dW_s \right]}_{\mathbb{E}[dW_s]=0} \right)^2 \right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}\left[ \left( \int_0^t \frac{g_s}{\alpha_s} dW_s \right)^2 \right] \quad \quad | \quad \quad \text{Ito Isommetry} \\ &= \int_0^t \left(\frac{g_s}{\alpha_s}\right)^2 ds \end{align}\)

With this result, we can now go back to our original definition of $y_t = x_t / \alpha_t$ and substitute back to get the diffusion of the original, non-martingale process, \(\begin{align} \mathbb{V}[y_t-y_0] &= \mathbb{V} \left[\frac{x_t}{\alpha_t}-\frac{x_0}{\alpha_t} \right] \\ &= \frac{1}{\alpha_t^2} \mathbb{V} \left[x_t-x_0 \right] \\ &= \int_0^t \left(\frac{g_s}{\alpha_s}\right)^2 ds \\ & \downarrow \\ \sigma_t^2 &= \alpha_t^2 \int_0^t \left(\frac{g_s}{\alpha_s}\right)^2 ds \end{align}\)

Going from flow matching to diffusion is easier once we have one correspondence. To obtain the drift parameter $f$, we simply determine the inverse function, \(\begin{align} \alpha_t &= \exp\left[ -\int_0^t f_s ds \right] \\ \log \alpha_t &= -\int_0^t f_s ds \\ -d\log \alpha_t &= f_t \\ \end{align}\) and to obtain $g_t$ from an existing flow, we have \(\begin{align} \sigma_t^2 &= \alpha_t^2 \int_0^t \left(\frac{g_s}{\alpha_s}\right)^2 ds \\ \frac{\sigma_t^2}{\alpha_t^2} &=\int_0^t \left(\frac{g_s}{\alpha_s}\right)^2 ds \\ d\left[\frac{\sigma_t^2}{\alpha_t^2}\right] &= \left(\frac{g_t}{\alpha_t}\right)^2 \\ 2 \frac{\sigma_t}{\alpha_t} d\left[\frac{\sigma_t}{\alpha_t}\right] &= \frac{g_t^2}{\alpha_t^2} \\ 2 \ \sigma_t \ \alpha_t \ d\left[\frac{\sigma_t}{\alpha_t}\right] &= g_t^2 \\ 2 \ \sigma_t \ \alpha_t \ \frac{\dot{\sigma}_t \alpha_t - \sigma_t \dot{\alpha}_t}{\alpha_t^2} &= g_t^2 \\ 2 \ ( \sigma_t \dot{\sigma}_t - \sigma_t^2 \ \text{d}\log\alpha_t)&= g_t^2 \\ \end{align}\)

The identities above allow us to seamlessly translate flow matching schedules $\alpha_t, \sigma_t$ to OU diffusion schedules $f_t, g_t$ and vice versa.

In code this looks like this:

"""

Flow Matching to Diffusion SDE Conversion

FM: x_t = (1 - t) * x + t * noise

SDE: dX_t = -f(t, X_t) dt + g(t, X_t) dW_t

f = - ∂_t log(α_t) = = - dlog(α_t) = - 1 / (1 - t + 1e-6)

g_t^2 = 2 (σ_t ∂_t[σ_t] - σ_t^2 dlog[α_t])

"""

alpha_t = lambda t: 1 - t

dalpha_t = lambda t: -1

dlog_alpha_t = lambda t: -1 / (1 - t + 1e-6)

sigma_t = lambda t: 0.001 + 0.999 * t

dsigma_t = lambda t: 0.9999

diff_t = lambda t: 1.0

f_t = lambda t: dlog_alpha_t(t) # f(t) already incorporates - sign

g_t = lambda t: (

2

* (

sigma_t(t) * dsigma_t(t)

- sigma_t(t) ** 2 * dalpha_t(t) / (alpha_t(t) + 1e-6)

)

+ 1e-6

).pow(0.5)

So far, we’ve only considered the vanilla score matching. But we’ve seen from this blog post that we can in fact extract the score out of a flow model. This implies that we can run a SDE purely from a flow matching model. In this case the flow sampling that was previously an ODE can be extended to an SDE, like so \(\begin{align} dx_\tau &= v_\theta(x_\tau, \tau) \\ & \downarrow \text{add stochasticity} \ \epsilon_\tau \\ dx_\tau &= \big(v_\theta(x_\tau, \tau) -\underbrace{\frac{1}{2}\epsilon_\tau^2 \nabla_x \log p_{\theta}(x_\tau, \tau)}_{\text{stochastic control}}\big) \ d\tau + \underbrace{\epsilon_\tau dW_\tau}_{\text{extra noise}}\\ \end{align}\)

All that the augmented flow matching model does is add additional noise to sampling process which is then corrected by the additional score term $\nabla_x \log p_{\theta}$ which is extracted from the flow model. We can recover the original flow matching sampling with \(\begin{align} \quad dx_\tau &= \left[ (v_\theta(x_\tau, \tau) - \frac{1}{2}\epsilon_\tau^2 \nabla_x \log p_{\theta}(x_\tau, \tau)) \ d\tau + \epsilon_\tau dW_\tau \right]_{\epsilon_\tau=0} \\ &= v_\theta(x_\tau, \tau) \ d\tau. \end{align}\)

The nice thing is that we can scale $\epsilon_\tau$ up and down as we like, and the noise $\epsilon_\tau dW_\tau$ and the corrective score term automatically balance each other out.

Similarly, we can add extra noise to the SDE formulation as detailed in this blog post, \(\begin{align} dX_\tau = (-f_\tau x_\tau + \frac{1}{2}g_\tau^2(1+\eta_\tau^2)\nabla_x \log p_\theta(x_\tau, \tau))d\tau + \eta_\tau g_\tau dW_\tau \end{align}\)

While the double occurence of $\eta_\tau$ might seem daunting on first sight to translate into the flow matching framework, it actually is quite straightforward. All we have to remember is that the flow matching objective trains the model on the ODE of probability flow. Thus we can rearrange the terms such that \(\begin{align} dX_\tau &= (-f_\tau x_\tau + \frac{1}{2}g_\tau^2(1+\eta_\tau^2)\nabla_x \log p_\theta(x_\tau, \tau))d\tau \\ & \quad + \eta_\tau g_\tau dW_\tau \\ &= (\overbrace{-f_\tau x_\tau + \frac{1}{2}g_\tau^2\nabla_x \log p_\theta(x_\tau, \tau)}^{v_\theta(x_\tau, \tau)} + \frac{1}{2}\overbrace{g_\tau^2\eta_\tau^2}^{\epsilon_\tau^2} \log p_\theta(x_\tau, \tau))d\tau \\ & \quad + \underbrace{\eta_\tau g_\tau}_{\epsilon_\tau} dW_\tau \\ \end{align}\)

and so we can conclude that the last flow matching parameter $\eta_\tau$ can also be translated to the diffusion framework via $\epsilon_\tau = g_\tau \eta_\tau$.