Sinkhorn Iterations

Computing Wasserstein Distances

Computing the difference between two distributions is a problem commonly encountered in machine learning. Monte Carlo approximations of the KL divergence commonly suffer from the problem of sampling from the proposal distribution and computing relevant statistics with respect to the target distribution. In this case a problem can arise when the support of the proposal distribution from which the samples are drawn does not match the support of the target distribution. Intuitively one can image two Normal distributions with vastly different means and similar covariance matrices. It will be very hard to draw a sample from the source distribution which also lies in the support of the target distribution. The KL divergence is not symmetric in that respect since swapping the two distributions will give different loss values. The non-symmetry is the reason the KL divergence is not considered a distance, but only a divergence.

Ultimately, we are dependent on the proposal distribution in the KL divergence to cover the support of the target distribution with sufficient probability mass such that we can sample from the relevant portions of the target distribution. For the more interested reader, I would recommend reading up on Forward and Backward KL divergences and the behaviour of mode-seeking and mean-seeking.

The Wasserstein distance provides a remedy for this by posing a different distance measure: the earth mover distance. Contrary to the KL divergence, the Wasserstein distance asks how much probability mass we need to move around the source target distribution such that it matches the target distribution. This notion is independent of the support of the distribution and one of the reasons why it has become popular in GAN’s.

The only extra information we need is a cost matrix which determines how expensive it is to move probability mass from one point in the source distribution to another point in the source distribution. In the analogy of moving mass around, one can imagine that it is more work to move some mass for five ‘steps’ than it is to just move the same mass one step away. While the earth mover distance can be derived for continuous distributions, it’s easiest to visualize with discrete distributions and moving probability mass between the ‘buckets’ of the discrete distributions.

Let’s define two probability vectors $p$ and $q$ which both define a categorical distribution in $\mathbb{R}_+^{d}$. Both these probability vectors form a simplex through two constraints which apply to them (analogously for $q$): \(\begin{align} p^T \mathbb{1} &= 1 \\ p_i & \in \mathbb{R}_+ \end{align}\)

The second thing we need is a cost matrix $C$ for the objective function of the Wasserstein distance which characterizes how expensive it is to move probability mass from one category of a categorical distribution to another. We can simply use different Euclidean distance between two vectors $x$ and $y$ for that: \(\begin{align} c_{ij} = |(x_i-y_j)| \quad \text{or} \quad c_{ij} = ||(x_i-y_j)|| _2^2 \ \forall i, j \in \{1, \ldots, d\} \end{align}\)

The cost matrix $T$ for categorical distributions should be a symmetric matrix which increases its values as it moves away from the diagonal. But of course if you are dealing with a different transport problem, the cost matrix could be different and non-symmetric depending on your transport manifold.

For a categorical distribution with three possible events (intuitively bins) ${ 0, 1, 2}$ it should be: \(\begin{align} C = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 1& 0 & 1\\ 2 & 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{align}\)

All this cost matrix says is that we have to ‘hop’ twice to move probability mass from bin 0 to bin 2.

The final component of the Wasserstein distance is the coupling matrix $T$ which is defined through a polyhedral set \(\begin{align} U(p, q) = \{ T \in \mathbb{R}_+^{d \times d} \quad | \quad T \mathbb{1} = p, T^T \mathbb{1} = q \} \end{align}\) A polyhedral set refers to a set of solutions which are constrained by a finite number of half-spaces. Half-spaces can be created through inequality constraints which form a convex set in our case.

Remember that $p$ and $q$ are both distribution vectors. The purpose of the coupling matrix $T$ is to quantify a way to move probability mass about the source distribution such that it becomes equal to the target distribution. The next logical step should be to guarantee that a valid coupling matrix $T$ moves the exact amount of probability mass such that we obtain both the distribution vectors $p$ and $q$ if we sum up the rows and columns of the matrix.

For a small example let $p = [ 1, 0, 0]^T$ and $q = [ 0, 0, 1]^T$. The only valid coupling matrix $T$ would be \(\begin{align} T &= p q^T\\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \Rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} = T \mathbb{1} = p \\ & \qquad \quad \Downarrow \\ & \quad \ \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \\ & \quad = T^T \mathbb{1} = q \end{align}\)

A closer look at the coupling matrix shows the expected behaviour that we move all the probability mass from bin 1 in $p$ to bin 3 in $q$.

The Wasserstein distance between two distributions is defined as the minimum of the inner Frobenius product $\langle \cdot, \cdot \rangle_F$ of the coupling matrix $T$ and the cost matrix $C$: \(\begin{align} \mathcal{W}(p,q) := \min_{T\in U(p,q)} \left\langle T; C \right\rangle_F. \end{align}\)

In the equation above, the membership of $T \in U(r,c)$ contains the constraints that $T$ has to be a valid coupling matrix.

The hard part is now to find the coupling matrix $T$ which accurately represents the probability mass that we have to move around in $p$ to arrive at the distribution vector $q$. There is a very large number of possible coupling matrices $T$ which all result in a valid transport of the probability mass, yet we are interested in the coupling matrix $T$ which transports the least amount of probability mass!

Since we are computing the Frobenius norm with respect to the cost matrix $C$ we want the Wasserstein distance to be as small as possible, meaning that we want to move as little probability mass as possible on the off-diagonal entries in $T$. We don’t want an artificially high cost because of valid, though unreasonable, transport plans if two distributions are the same except for a tiny fraction of probability mass.

We could solve the problem above with linear programming since it’s simply finding the minimum of a linear program given a series of inequality constrains on the coupling matrix. Linear programming becomes infeasible and difficult for large solution spaces and furthermore is not differentiable which makes this solution unattractive for the use in gradient-based optimization schemes.

The solution of our original linear program would result in a sparse solution on one of the vertices given by the constraints. One can imagine this as searching for the absolute perfect solution in the remotest corner of the simplex. But we could ask ourselves in the age of approximate function fitting and empirical risk minimization, whether we really require such a perfect solution. Could we arrive at an easier to optimize objective function if we were to accept a slightly less accurate solution?

Enter Sinkhorn distances as optimal transport with entropic constraints!

The answer is yes with the help of entropic regularization. We therefore augment the original convex set: \(\begin{align} U_\lambda (p,q) &= \{ T \in U(p,q) \quad | \quad \text{KL}[T || pq^T] \leq \lambda \} \\ &= \{ T \in U(p,q) \quad | \quad H[T] \geq H[p] + H[q] - \mu\} \subset U(p,q) \end{align}\)

From information theory we know that the mutual information of two random variables $X$ and $Y$, should they follow a joint distribution, is defined as \(\begin{align} I[ p(x), p(y)] &= \text{KL}[p(x,y)||p(x), p(y)] \\ &= \int \int p(x,y) \log \frac{p(x,y)}{p(x)p(y)} dx dy \\ &= \int p(x,y) \log p(x,y) dx dy - \int p(x,y) \log p(x) dx dy - \int p(x,y) \log p(y) dx dy \\ &= -H[p(x,y)] - \int p(x) \log p(x) dx - \int p(y) \log p(y) dy \\ &= -H[p(x,y)] + H[p(x)] + H[p(y)] \end{align}\)

Given the fact that we construct the coupling matrix $T$ from both $p$ and $q$, and it therefore represents a joint probability distribution between $p$ and $q$, we can derive the additional constraints in the augmented convex set.

Analogously, we can define the same equations in our specific case for our joint probability $T$ and marginal probability vectors $p$ and $q$: \(\begin{align} \text{KL}[T||pq^T] &\leq \lambda \\ -H[T] + H[p] + H[q] &\leq \lambda \\ H[T] &\geq H[p] + H[q] - \lambda \end{align}\)

This is similar to how trust regions in optimization and reinforcement learning work. From an information theoretic point of view, the coupling matrix $T$, which we are optimizing, should not move too far from the joint probability distribution $pq^T$. We thus construct a trust region in terms of the KL divergence and parameter $\lambda$ in which we can freely optimize but not move too far away from our initial value. The aim of the original optimization is to find a transport scheme which minimizes the entropy of the coupling matrix $T$ due to the sparse solution on the vertices of the probability simplex.

The additional constraint forces the entropy of the coupling matrix $T$ not to fall below a certain threshold. The values of $H[p]$, $H[q]$ and $\lambda$ are all fixed and thus $H[T]$ should not fall below the combinations of these values. Therefore the optimization is discouraged from finding sparse solutions, as for example with the L1-norm, and encouraged to find a smooth transport plan $T$.

If $\lambda \rightarrow \infty$, the constraint disappears and the entropy of the coupling matrix will result in the same solution as the linear program since $H[T] \in \mathbb{R}_+$.

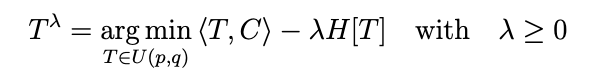

An alternative objective function would therefore be the following: \(\begin{align} T^\lambda = \text{argmin}_{T \in U(p,q)} \left\langle T , C \right\rangle - \lambda H[T] \quad \text{with} \quad \lambda \geq 0 \end{align}\)

Adding the original marginal constraint $T \mathbb{1} = p$ and $T^T \mathbb{1} = q$ and forming the Lagrangian gives us a convenient objective function: \(\begin{align} \mathcal{L}(T, \alpha, \beta) &= \left\langle T, C \right\rangle_F + \lambda H[T] + \alpha^T (T^T \mathbb{1} - q) + \beta^T (T \mathbb{1} - p) \\ &= \sum_{ij} t_{ij} c_{ij} + \lambda \sum_{ij} t_{ij} \log t_{ij} + \sum_i \alpha_i ( \sum_j t_{ij} - p_j) + \sum_i \beta_i ( \sum_j t_{ij} - q_i) \end{align}\)

The derivative $\partial \mathcal{L} / \partial t_{ij}$ yields \(\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial t_{ij}} &= c_{ij} + \lambda (\log t_{ij} + 1) + \alpha_i + \beta_i \stackrel{!}{=} 0 \\ \log t_{ij} &= - \frac{1}{\lambda} c_{ij} - 1 - \frac{1}{\lambda} \alpha_i - \frac{1}{\lambda} \beta_i \\ t_{ij} &= \exp \left[ - \frac{1}{\lambda} \alpha_i \right] \exp \left[-\frac{1}{\lambda} c_{ij}-1 \right] \exp \left[ - \frac{1}{\lambda} \beta_i \right] \end{align}\)

Now Sinkhorn’s theorem enters the plot. Sinkhorn’s theorem states that if a matrix $A$ has strictly positive elements, then there exist two diagonal matrices $D_1$ and $D_2$ with strictly positive diagonal elements such that $B = D_1 A D_2$ is doubly stochastic. Applying this to our problem, we have $T$ which by definition only has positive elements, and the diagonal matrices $\exp[ \text{diag}[ - 1/\lambda \cdot \alpha]]$ and $\exp [ \text{diag}[ - 1/\lambda \cdot \beta]]$. The diagonal matrices arise from the constraint on the rows and columns of the coupling matrix $T$. All of these matrices are the element-wise negative exponential which makes their entries by construction strictly positive. For the product of these three matrices, the result will be a double stochastic matrix $B$, which is defined by the properties $B\mathbb{1} = \mathbb{1}$ and $B^T\mathbb{1} = \mathbb{1}$.

We can rewrite the objective function in such a way that it reflects the Sinkhorn’s theorem: \(\begin{align} T = \text{diag}(u) K \text{diag}(v) \end{align}\) with \(\begin{align} K &= \exp[- \frac{1}{\lambda}C -\mathbb{1}\mathbb{1}^T ] \\ \text{diag}(u) &= D_1 = \text{diag}(\exp[ - \frac{1}{\lambda} \alpha]) \\ \text{diag}(v) &= D_2 = \text{diag}(\exp[ - \frac{1}{\lambda} \beta]). \end{align}\)

By plugging $T = \text{diag}(u) K \text{diag}(v)$ into our constraints $p = T \mathbb{1}$ and $ q = T^T \mathbb{1}$, we obtain the following element-wise updates: \(\begin{align} p &= \text{diag}(u) K \text{diag}(v) \mathbb{1} \\ q &= \text{diag}(u) K^T \text{diag}(v) \mathbb{1} \\ p_i &= u_i (Kv)_i \\ q_j &= v_j (K^Tu)_j \end{align}\)

By realigning the equations to $u$ and $v$, we obtain the alternating update rules: \(\begin{align} v_j & \leftarrow p_j / (K^T u)_j \\ u_j & \leftarrow q_j / (K v)_j \end{align}\) which can be rewritten into the element-wise operations \(\begin{align} v & \leftarrow p \oslash (K^T u) \\ u & \leftarrow q \oslash (K v) \end{align}\) where $\oslash$ is the element-wise division of two vectors.

Unfortunately, it turns out that these iterations are numerically not especially stable. The repeated divisions and multiplications can lead to numerical under- or overflows. Just imagine multiplying $0.1^{100}$ and you’ll quickly see that numerical issues can arise due to a limited bit number.

In order to stabilize the computations, the logarithm is used. For numerical computations, the logarithm has the nice practical property that it turns multiplications and divisions into additions and subtractions. \(\begin{align} \log v & \leftarrow \log p - \log[K^T u] \\ \log u & \leftarrow \log q - \log[K v] \end{align}\)

The logarithm of the vector matrix multiplication $\log[K^Tu]$ and $\log[Kv]$ need some extra handling. For simplicities sake, we will continue the derivation for $\log[Kv]$ but it holds for $\log[K^Tv]$ as well: \(\begin{align} \log[Kv]_i &= \log\left[ \sum_j K_{ij} v_j \right] \\ &= \log\left[ \sum_j \exp\left[-\frac{1}{\lambda}C_{ij} - 1 \right] v_j \right] \\ &= \log\left[ \sum_j \exp\left[-\frac{1}{\lambda}C_{ij} - 1 + \log v_j \right] \right]. \end{align}\)

The computation log-sum-exp is implemented in many numerical software packages and utilizes an additional trick to stabilize the computation. When we exponentiate very large or very small numbers (e.g. $\pm 10^10$) it can quickly happen that we encounter under- or overflows since such numbers go to either zero or infinity and we encounter the problem of represents very small or very large numbers with limited number of bits. Yet, this was precisely what we wanted to circumvent by applying the log to our update rules. Fortunately, we can simply subtract the maximum value inside the log-sum-exp operation and add it back on the outside. A small algebraic proof follows here which $x_{max} = \max { x_0, x_1, x_2, \ldots x_N}$: \(\begin{align} & \log \left[ \sum_i \exp[x_i] \right] \underbrace{+ x_{max} - x_{max}}_{=0} \\ & \log \left[ \sum_i \exp[x_i] \right] + x_{max} + \log \exp[ -x_{max}] \\ = & \log \left[ \sum_i \exp[x_i] \exp[ -x_{max}] \right] + x_{max} \\ = & \log \left[ \sum_i \exp[x_i -x_{max}] \right] + x_{max}. \end{align}\)

Intuitively, the log-sum-exp trick rescales the terms which are exponentiated into the well-behaved area around zero. This rescaling is then undone by simply adding the maximum value back. This updated computations of the log-sum-exp is done in most linear algebra packages under the hood.

Let’s get back to our original problem of computing the log of the matrix-vector product. \(\begin{align} \log[Kv]_i = \log\left[ \sum_j \exp\left[-\frac{1}{\lambda}C_{ij} -1 + \log v_j \right] \right]. \end{align}\)

We can compute the logarithmized matrix vector product by simply adding $\log v$ to each row of the rescaled cost matrix $C$ and the log-sum-exp trick is applied automatically. \(\begin{align} \log v & \leftarrow \log p - \log \left[ \sum_{rows} \left[ - \frac{1}{\lambda}C + \log u \right] \right] \\ \log u & \leftarrow \log q - \log \left[ \sum_{rows} \left[ - \frac{1}{\lambda}C + \log v \right] \right] \end{align}\)

The Sinkhorn iterations give us a way to compute the optimal transport plan. But we still have to compute the gradients for these iterations if we want to use them in gradient based optimization schemes. Remember that we used the Sinkhorn iterations in the first place to find a transport plan for which the gradient of the cost function with respect to the transport plane is zero, i.e. $\smash{\partial \mathcal{L}/ \partial t_{ij} \stackrel{!}{=}0}$. The vectors $u$ and $v$ were used as short-hand replacements for the exponentiated $\alpha$ and $\beta$ dual variables. The entire point of using duality in optimization is that we can solve an alternative optimization problem, the dual with the dual variables (in our case $\alpha$ and $\beta$), and the solution will be equivalent to our original optimization problem, the primal (given certain properties and constraints, into the detail of which I won’t go here). \(\begin{align} \partial \mathcal{L}/ \partial t_{ij} & \stackrel{!}{=}0 \\ \Downarrow \\ u = \exp[-\frac{1}{\lambda}\alpha] \ & , \ v = \exp[-\frac{1}{\lambda}\beta] \\ & \Downarrow \\ \alpha = -\lambda \log u \ & , \ \beta = -\lambda \log v \end{align}\)

Once we found $\alpha$ and $\beta$ we can plug them back into the original objective function $\mathcal{L}$ and we can compute the gradients with respect to the distributions at hand: \(\begin{align} \nabla_q\mathcal{L} &= \nabla_q \left[ \left\langle T, C \right\rangle_F + \lambda H[T] + \alpha^T(T^T\mathbb{1} - q) + \beta^T (T\mathbb{1} - p) \right] \\ &= \alpha \\ &= - \lambda \log u \end{align}\)

Now that we have the gradient $\nabla_q \mathcal{L}$ for each ‘bin’ in the proposal probability vector $q$ we can update this vector with stochastic gradient descent and fit it to the probability vector $p$.

How does all of this look in code? Well … here you go

import numpy as np

import torch

import ot

import math

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Tensor = torch.FloatTensor

p = Tensor([0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4]) # the target distribution we want to approximate

# Bunch of different initial distributions used for testing

# q = torch.nn.Parameter(Tensor([0.1, 0.25, 0.25, 0.4]))

q = torch.nn.Parameter(Tensor([0.4 , 0.2, 0.3, 0.1]))

# q = torch.nn.Parameter(Tensor([0.7, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1]))

# q = torch.nn.Parameter(Tensor([0.7, 0.2, 0.05, 0.05]))

# q = torch.nn.Parameter(Tensor([0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4

lambda_reg = 10 # larger values reduce entropy term -> 1/lambda_reg

# Use python optimal transport library to check whether cost functions is computed correctly as reference

print('Python Optimal Transport')

dist = np.arange(q.shape[0])

C = np.abs(np.expand_dims(dist, axis=1) - np.expand_dims(dist, 0))

P = ot.sinkhorn(p.data.numpy(), q.data.numpy(), C, reg=1./lambda_reg, method='sinkhorn')

print('dist:', np.sum(P * C), np.sum(P))

print()

Now we’ve set up the the two distributions and are ready to optimize.

The Sinkhorn iteration function takes the two distributions performs the Sinkhorn iterations and returns the gradient for the proposal distribution which is computed from alpha:

def sinkhorn_iteration(p, q, lambda_reg, log=True): # the main sinkhorn iteration function

'''

:param a: target / parameterized distribution

:param b: source distribution

:return: Wasserstein distance between source / parameterized distribution and target distribution

Solves the transport problem

argmin <P, C> + 1/lambda_reg H[P}

'''

assert p.shape == torch.Size([4])

assert q.shape == torch.Size([4])

dist = torch.arange(p.shape[0]).float()

C = torch.abs(dist.unsqueeze(1) - dist.unsqueeze(0))

K = torch.exp(-lambda_reg * C-1)

alpha = torch.ones_like(p)/4

beta = torch.ones_like(q)/4

log_alpha = torch.ones_like(p)*(-math.log(4))

log_beta = torch.ones_like(p)*(-math.log(4))

if not log:

for iter in range(200):

last_u = alpha

alpha = p / (K @ beta)

beta = q / (K @ alpha)

if torch.mean(torch.abs(alpha - last_u)) < 0.05:

break

elif log:

for iter in range(200):

last_log_alpha = log_alpha

log_alpha = torch.log(p) - torch.logsumexp(-lambda_reg*C -1 + log_beta, dim=1)

log_beta = torch.log(q) - torch.logsumexp(-lambda_reg*C -1 + log_alpha, dim=1)

if torch.mean(torch.abs(log_alpha - last_log_alpha)) < 0.005:

break

alpha = log_alpha.exp()

beta = log_beta.exp()

P = torch.diag(alpha) @ K @ torch.diag(beta)

d = torch.sum(P * C)

grad = torch.log(alpha)/lambda_reg #- torch.mean(torch.log(alpha))/lambda_reg

return d, P, grad

Finally we’ll use the optimizer provided by PyTorch to do a couple of hundred steps to let the proposal distribution converge to the true distribution. While we’re at it, we’ll also plot a couple of sanity checks such as the distributions still summing up to one

optim = torch.optim.SGD([q], lr=0.001)

epochs = 2000

for epoch in range(epochs):

optim.zero_grad()

dist, P, grad = sinkhorn_iteration(p, q, lambda_reg)

q.grad = - grad

optim.step()

if epoch % (epochs//10) == 0: print('Epoch: ', epoch, dist.detach(), torch.sum(P).detach(), q.detach())

if epoch <10: print('Epoch: ', epoch, dist.detach(), torch.sum(P).detach(), q.detach())

print(q.detach(), 'sum(source_dist)=', torch.sum(q).detach().item())

Interestingly, I was only able to make it work with the plain SGD optimizer. ADAM for some reason went NaN on my after a couple of iterations. I suspect it has to do something with the second-order estimations and maybe the gradient I provide somewhere let’s these second-order moments explode.

Up to this point we had a look at discrete distributions and how to compute an optimal transport plan. It turns out, that the optimal transport plan for continuous distributions (at least for the Normal distribution) is quite compact and doesn’t require an auxiliary optimization problem via the Sinkhorn iterations.