RSA Cryptography:

The Math

The math that ensures that it's none of your business

The advantages of public private key encryption

We are all used to having access to secure communication that we seldomly ask ourselves how the encryption that keeps prying eyes from reading our messages actually works.

What is in fact the best way to establish secure communications?

In most secret agent movies, there exists a cypher which allows the hero, or the villain, to decode a hidden or encrypted text into its original meaning. Either it’s selecting specific letters from the newspaper or it’s running a tremendously exciting looking algorithm over some text files on a computer. But in both cases the hero, or the villain, is already in possession of the knowledge how to decrypt the encrypted text.

But how did he obtain it knowledge to decrypt the encrypted text?

Certainly, it’s very dangerous to simply send the decryption key, whatever form it may take, through the plain mail. It could get intercepted and copied, rendering any further encrypted communication worthless, as the copied decryption key allows the interceptor to decrypt of the secret message.

The answer lies in asymmetric cryptography.

The best analogy that I can think of is, that the person who wants to receive encrypted messages passes out publicly an abundance of open locks to which only he has the key to unlock them. So another person who wants to send you encrypted messages can simply pick up a publicly available open lock, but the message inside, lock it and send you the message. Since only you have the key to all of these locks, you’re the only one who can open the lock and actually look at what you were sent. If you were to reply, you would simply pick up a lock that the other persons has publicly on offer, lock you message up and send him or her your message.

This concept is nice in theory, but how would it work technically and provable mathematically? Let us establish some basics first which will be important down the road.

Modulo: The Secret Sauce of RSA IMHO

The modulo operator $x \ mod \ n$ takes any number $x$ and returns the remainder after the division with $n$. Let’s say you want to know $x \ mod \ n$, then we can represent $x$ as $x= k n + r$ for an integer $k$ and the remainder $r$. The modulo operator is in fact not very complicated and it should be clear after a few examples:

\[\begin{aligned} x \mod \ n &= r \quad \text{since} \quad && x = k * n + r && \quad \text{with} \quad k \in \mathbb{N}, r \in \mathbb{N} \\ \\ 9 \mod \ 2 &= 1 \quad \text{since} \quad && 9 = 4 * 2 + 1 && \quad \text{with} \quad k=4, r=1 \\ 13 \mod \ 2 &= 1 \quad \text{since} \quad && 13 = 6 * 2 + 1 && \quad \text{with} \quad k=6, r=1 \\ \\ 5 \mod \ 3 &= 2 \quad \text{since} \quad && 5 = 1 * 3 + 2 && \quad \text{with} \quad k=1, r=2 \\ 8 \mod \ 3 &= 2 \quad \text{since} \quad && 8 = 2 * 3 + 2 && \quad \text{with} \quad k=2, r=2 \\ \end{aligned}\]I chose the examples with care to highlight a natural property of the modulo operator which makes it so appealing to cryptography. Namely, that we apply the modulo operator on different numbers and will obtain the same remainder. If you’re only left with the number $n$ and the remainder $r$, there is no way to obtain the original number $x$. The modulo operator is basically a one way operation which hides the original number $x$! The properties of the modulo function that will be important to us only consider large integer values.

Coprime Integers

The next ingredient that is required are coprime integers. ‘Coprime’ might sound threatening and complicated but in fact the definition is quite simple. Two integer numbers are coprime if their greatest common divisor is 1, $\text{gcd}(a, b)=1$ for $a, b \in \mathbb{N}$.

In laymen’s terms, this means that both numbers are divisible into an integer only by the number of one. So for example, 3 and 5 are coprime because 1 is the largest integer divisor of both of them. The numbers 3 and 15 and not coprime because the greatest common denominator is 3. The latter example is still divisible by 1 as well, but we’re talking about the greatest common divisor of two integer numbers.

Eulers Totient

For $n \in \mathbb{N}$, Euler’s totient is given as the number of integer numbers $m$ that are in the set

\[\begin{align} \phi(n) = \{m \in \mathbb{N} \ | \ 1 \leq m \leq n, \text{gcd}(m, n) = 1 \} \end{align}\]which essentially means that we want the number of integers that are smaller than $n$ and are coprime to $n$. As an example let’s look at \(\phi(9) = | \{1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8 \} | = 6\). The numbers 3, 6 and 9 are not members of $\phi(9)$ because their greatest common divisor is 3, so the restriction $\text{gcd}(\{ 3,6,9 \}, 9) =1$ does not hold.

More importantly for our application, Euler’s totient is a multiplicative function for two numbers which are relatively prime, or coprime, to each other.

\[\begin{align} \phi(n) = \phi(pq) = \phi(p) \phi(q) \quad ; \text{gcd}(p, q)=1 \end{align}\]Also, taking Euler’s totient of a prime number $p \in \mathbb{P}$ returns $\phi(p) = p-1$ since a prime number is only divisible by 1 or itself and thus every number before $p$ falls into the category of Euler’s totient. This will be important later for the RSA algorithm …

Eulers Theorem: The Bedrock of RSA

The impressive Leonhard Euler ( I mean come on, the guy lived 250 years ago and so much of our modern technological applications are based on his math) found out that if $n$ and $a$ are coprime, the following identity holds: \(\left[ a^{\phi(n)} = 1 \right] \mod \ n.\)

The notation $[ \ldots ] \mod n$ means that we apply the modulo equally to both sides. The notation $\ldots = \ldots (\mod n)$ is more common but I like my paranthesis to clearly delineate what operator we apply to what.

Now it turns out that we can massage Euler’s Theorem into a very useful form, namely \(\begin{align} \Big[ a^{\phi(n)} &= 1 \Big] \mod \ n \\ \Big[ a^{k\phi(n)} &= 1 \Big] \mod \ n \\ \end{align}\)

Right here we smuggled in the integer number $k$ in the exponentiation. In order to prove the validity of this step, we can construct the following ‘proof’ (Hey, I ain’t no mathematician, but at least the math checks out),

\(\begin{align} \Big[ a^{k\phi(n)} = 1 \Big] \mod \ n \\ \Big[ {\big( a^{\phi(n)} \big) }^k = 1 \Big] \mod \ n \\ \Big[ \prod_i^k {\big( a^{\phi(n)} \big) } = 1 \Big] \mod \ n \\ \end{align}\) for which we can now employ the transitivity rule which states that \(\begin{align} & \Big[ ab \Big] \mod n \\ =& \Big[ [a] \ \text{mod} \ n \cdot [b] \ \text{mod} \ n \Big] \mod n \\ \end{align}\)

which gives us

\[\begin{align} \Big[ \prod_i^k {\big( a^{\phi(n)} \big) } = 1 \Big] \mod \ n \\ \Bigg[ \prod_i^k \Big( \Big[ \underbrace{a^{\phi(n)} \Big] \ \text{mod} \ n}_{=1} \Big) = 1 \Bigg] \mod \ n \\ \Bigg[ \prod_i^k \Big( 1 \Big) = 1 \Bigg] \mod \ n \\ \Bigg[ 1 = 1 \Bigg] \mod \ n. \end{align}\]which proves that we can add an integer multiplier in the exponent. Carrying on we have

\[\begin{align} & \Big[ a^{\phi(n)} = 1 \Big] \mod \ n \\ & \Big[ a^{k\phi(n)} = 1 \Big] \mod \ n \quad \Big| \cdot a \\ & \Big[ a^{k \phi(n)+ 1} = a \Big] \mod \ n \\ \end{align}\]The equation above tells us that for some integer number $k$ about which we don’t really care and the number $n$ we can exponentiate the number $a$ with $k \phi(n)+1$ and under the $\text{mod} \ n$ regime we will obtain the same number $a$. The cool thing that Euler’s Theorem allows us to do is that we can obviously factorize, respectively construct, the exponent $k \phi(n)+1$ in any way we want.

And this is where we finally get to the main RSA algorithm.

RSA Encryption

The Rivest-Shamir-Adleman cryptosystem leans heavily, and almost exclusively, on Euler’s theorem to enable an asymmetric cryptographic system. It starts out by taking a message, which are just numbers for computers, and exponentiating it with the secret key $e$ and applying the modulo operator $\text{mod} \ n $ to it to generate an encrypted cypher text $c$, \(\begin{align} \text{Encryption}: \quad c = [ x^e ] \mod n. \end{align}\)

We can conclude that we only need the encryption key $e$ (which is a number) and the modulo basis $n$ (which is also just a number) to be public to enable anybody to encrypt a message for us. The almost identical operation, albeit with the secret key $d$, is performed to decrypt the cypher message $c$, \(\begin{align} \text{Decryption}: \quad x = [ c^d ] \mod n \end{align}\)

The big question is obviously whether there is a strict one-to-one correspondence between the encryption and the decryption. Because a cryptographic system which maps multiple messages into the same decrypted message is absolutely worthless. To show this, we can again employ Euler’s theorem to guarantee the needed one-to-one correspondence, such that

\[\begin{align} [ c^d &= x ] \mod n \\ \Big[ \big( [ x^e ] \mod n \big)^d &= x \Big] \mod n \\ \Big[ \prod^d_i \big( [ x^e ] \mod n \big) &= x \Big] \mod n \quad \\ \Big[ \prod^d_i x^e &= x \Big] \mod n \quad \text{(Transitivity Rule)} \\ \Big[ \big( x^e \big)^d &= x \Big] \mod n \\ \Big[ x^{ed} &= x \Big] \mod n \\ \end{align}\]Thus if we are able to find a corresponding exponent in our encryption/decryption scheme that fulfills Euler’s theorem, we have a wonderful asymmetric cryptographic system which checkmarks all the requirements we wanted:

\[\begin{align} \Big[ x^{ed} &= x \Big] \mod \ n \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad \Big[ a^{k \phi(n)+ 1} = a \Big] \mod \ n \end{align}\]The beauty of the modulo operator is that it’s really hard to guess the correct $d$ since there are an infinite number of possible $d$’s due to the arbitrary $k$ for which the modulo operator returns a possible correct $x$.

The only remaining question is now how to choose the modulo basis $n$ of which we want to compute Euler’s totient efficiently. Naturally, we want $n$ to be very large such that an interceptor can’t simply try out all the $k$’s and Euler’s totient $\phi(n)$’s by brute force, since the RSA key generation scheme for $e$ and $d$ is public. Instead we want a very, very large number $n$ for which it is almost impossible to determine the totient $\phi(n)$ by brute force, but which we construct in such a way that we know the totient in single evaluation during the key generation.

For this we will use the previousuly stated property of the totient that if two numbers are coprime to each other, we can simply factorize the totient into the multiplicative components. Furthermore we can leverage the fact, and this is extremely important for the RSA cryptographic system, that Euler’s totient of a prime number $p$ is just $\phi(p)= p-1$ since a prime number is integer divisible only by itself and one. This means that Euler’s totient for prime numbers is just the respective prime number reduced by one, which means that every number before the prime number is coprime to it as the greatest common divisor of a prime number is 1.

Thus if we construct $n=pq$ from two very large, but distinct, prime numbers $p, q \in \mathbb{P}$, we can factorize the practically incalculable totient of $n$ into a fairly easily computable product, \(\begin{align} \phi(n) = \phi(p)\phi(q) = (p-1)(q-1). \end{align}\)

That means that the main effort of the RSA cryptographic system lies with the generation of two very large prime numbers which have to remain secret as they are used during the generation of the private key. Just to reiterate, computing Euler’s totient $\phi(n)$ for a very large $n$ is practically impossible at the moment (but let’s maybe wait for quantum computers), while the private knowledge of the two prime numbers $p$ and $q$ which constitute $n$ multiplicatively allows us to generate a correct private key quite easily. In fact after having generated $p$ and $q$ we can simply pick a super large $k$ and determine $d$ quite easily as $d=(k(p-1)(q-1)+1)/e$.

In order to get the mathematical equivalency that the encryption and subsequent decryption under the modulo $n$ operation is valid, all we have to do is find a $d$ for which holds

\[\begin{align} e d &= k \phi(n)+1 \\ e d &= k \phi(pq)+1 \\ e d &= k \phi(p) \phi(q) + 1 \\ e d &= k (p-1)(q-1) + 1 \\ \Big[ ed &= 1 \Big] \mod (p-1)(q-1) \\ \end{align}\]which tells us that we are indeed generating the private key $d$ with the private ingredients of $\phi(p)$ and $\phi(q)$ of our two secret prime numbers $p$ and $q$.

The last thing to check is that $a$ and $n$ are indeed coprime (not necessarily prime themselves) which happens with overwhelming probability as $n$ becomes increasingly large.

Signatures in RSA

An intriguing property of the public private key encryption is its ability to sign messages as a sender through the use of a cryptographic hash function.

A cryptographic hash maps data of an arbitrary size to a bit array of fixed size. It is by all practical means a seemingly random function, although it is in fact deterministic but people have spent a lot of time perfecting the ostensible randomness. Importantly, hash functions should be quick to compute, infeasible to reverse and to find two messages with the same hash and finally changing the input message slightly should return a completely different hash. Illustratively, hash functions permute input, cycle over it a couple of times and do all other crazy things to map the variable input length array into a fixed one.

But let’s get back to RSA …

A sender would send the message through a hash function $h = hash(x)$ and subsequently exponentiate it with the private key $d$. The receiver can then exponetiate the ‘decrypted’ hash again with the public key $e$ and take the modulo of it and compare it to his or her own hash of the sent message.

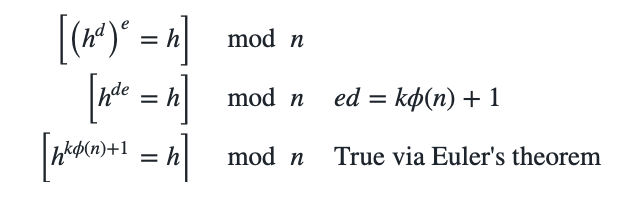

Mathematically, we can employ Euler’s theorem again, having defined the product of the private and public key as $ed = k \phi(n)+1$, to obtain

\[\begin{align} \Big[ {\big(h^d \big)}^e &= h \Big] \mod n \\ \Big[ h^{de} &= h \Big] \mod n \quad ed = k\phi(n)+1 \\ \Big[ h^{k\phi(n)+1} &= h \Big] \mod n \quad \text{True via Euler's theorem} \\ \end{align}\]Cha-Ching Baby …