Ito's (Di)Lemma

Or how to differentiate a function of a stochastic process.

Differentiability

Probably one of the most fundamental uses of calculus is the derivation of functions. A function $f$ is differentiable if the following value $f’(x)$ exists: \(\begin{align} f'(x) = \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \end{align}\) If we let $h$ go towards zero, a function is called differentiable, if the fraction converges towards some constant value.

Let’s look at an example of how this might work. We’ll need an additional mathematical trick called L’Hopitals rule which says that for evaluating the limit of a fraction we can simply derive both nominator and denominator with respect to the same variable and still obtain the valid result. Applying L’Hopitals rule often simplifies the computation of the derivative since we’re always working with the limit of a fraction.

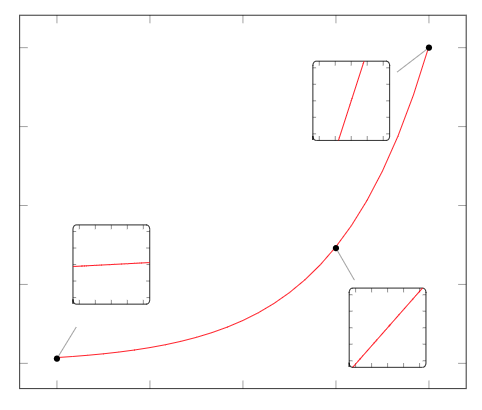

Let’s try to compute the derivative of the squared function $f(x) = x^2$: \(\begin{align} f'(x) &= \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \\ &= \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{(x+h)^2 - x^2}{h} \\ &= \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{x^2 + 2hx + h^2 - x^2}{h} \\ &= \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{\frac{\partial }{\partial h} \ 2hx + h^2}{\frac{\partial }{\partial h}h} \quad \quad \quad &&\Leftarrow \text{Applying L'Hopitals rule} \\ &= \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{2x + 2h}{1} && \Leftarrow \text{Evaluating $h$ to zero} \\ &= 2x \end{align}\) Sure enough it’s the correct result which we anticipated. In effect, we’re zooming infinitely far into the function and ask ourselves how the function changes in this tiny window $h$. Visually, this looks something like this for the exponential function $f(x) = e^x$:

What this functions tells us is that we can approximate an arbitrarily complex, differentiable function with a linear function for a extremely small window $\lim h \rightarrow 0 $. But in order for the function to be differentiable, the limit has to actually converge to a linear function as we decrease the window size $h$.

Unfortunately, for stochastic processes this is not as straight forward and we will require some more elaborate tools to show some notion of differentiability.

Stochastic Processes

In order to keep things simple in the following steps, we will work with the Brownian Motion.

Brownian motion $W_t$ is defined through the following properties:

- $W_0 = 0$

- Independent increments: covariance $\mathbb{C}[W_{t+u} - W_s, W_s] =0$ for $u \geq 0$ and $s \leq t$

- Gaussian increments: $W_{t+u} - W_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0, u)$

- Continuous paths in time $t$.

Now it turns out that there exists a stochastic differential equation which fulfills all of the properties above. This SDE in question is \(\begin{align} dx_t = dW_t = \epsilon \sqrt{dt} \quad \quad \quad ;\epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1) \end{align}\) Intuitively, we equate the infinitesimal change in $x_t$ with Brownian Motion which in turn is defined as the standard normally distributed random variable $\epsilon$ scaled by $\sqrt{dt}$. The problem of classical differentiability of stochastic processes lies precisely in this SDE as we defined the change with respect to $dt$. By defining the infinitesimal change $dt$ we are acknowledging that we could always use a shorter $dt$ and zoom even further into the time axis. After all, the infinitesimal change of the Brownian Motion $dW_t$ is defined as a limit in time not unlike the limit we used to show the differentiability of the quadratic function: \(\begin{align} dW_t = \lim_{\Delta t \rightarrow 0} W_{t + \Delta t} - W_t \quad \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \Delta t) \end{align}\) While $\Delta t$ goes rapidly towards zero, it will actually never be exactly zero. Thus, if we were to zoom into the time axis we would realize that the Brownian Motion keeps moving randomly for whatever time resolution we choose. In turns out that Brownian Motion actually has fractal properties which are probably the trippiest mathematical animations you can experience without doing actual acid.

No matter how far we zoom into the Brownian Motion, we will always encounter a Brownian Motion on a finer time scale since $dx_t$ moves randomly on any time scale we choose. Probably the best animation for that is directly from the Wikipedia page of Brownian Motion:

You might wonder: Well, why is that a problem with respect to classical differentiability? For that we can simply evaluate the differential \(\begin{align} \lim_{\Delta t\rightarrow 0} \frac{W_{t+\Delta t} - W_t}{\Delta t} \end{align}\) but alas, $W_t$ is by definition a Normally distributed random variable. So let’s have a look at the mean and variance of the differential operator: \(\begin{align} \lim_{\Delta t\rightarrow 0} \mathbb{E}\left[ \frac{W_{t+\Delta t} - W_t}{\Delta t} \right] &= \lim_{\Delta t} \frac{1}{\Delta t} \mathbb{E} [ \underbrace{W_{t+\Delta t} - W_t}_{\sim \mathcal{N}(0,\Delta t)} ] \\ &= \lim_{\Delta t} \frac{1}{\Delta t} 0 \\ &= 0 \end{align}\) and \(\begin{align} \lim_{\Delta t\rightarrow 0} \mathbb{V} \left[\frac{W_{t+\Delta t} - W_t}{\Delta t} \right] &= \lim_{\Delta t\rightarrow 0} \frac{1}{\Delta t^2} \mathbb{V} [ \underbrace{W_{t+\Delta t} - W_t}_{\sim \mathcal{N}(0,\Delta t)} ] \\ &= \lim_{\Delta t\rightarrow 0} \frac{1}{\Delta t^2} \Delta t \\ &= \lim_{\Delta t\rightarrow 0} \frac{1}{\Delta t} \\ &= \infty \end{align}\) Both the mean and the variance are possibly the worst values you can expect in terms of functional analysis. The mean is zero, indicating we have no derivative what so ever while the variance goes to infinity which is equally unusable. Ultimately, we can’t derive a Wiener process in the classical sense.

It turns out that Kiyosi Ito had a series of great insights that we can use. But before we can dive into his ideas, we first have to learn about Taylor expansions …

Taylor Expansion

The Taylor expansions or Taylor series is one of the most ubiquitous mathematical tools in applied math. Once at the DeepBayes summer school in Moscow, a fellow attendee and physicist said that if you have no clue what to do next with your equations, do a Taylor expansion and see if it gets you ahead.

The core idea of a Taylor expansion is to approximate a function locally around a root point with a series of terms which rely on the derivatives of the function. So for example a function might be a polynomial of order 10 but locally, we only need a quadratic function to approximate it quite well.

Mathematically, a Taylor expansion of a infinitely differentiable function $f(x)$ around a root point $x_0$ is defined as \(f(x)|_{x_0} = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{f^{(n)}(x_0)}{n!}(x-x_0)^n\) In order to keep things simple we will only work with a Taylor expansion of the second order, meaning that we will stop the sum after the term with the second order derivative. Practically, many problems are posed as linear or quadratic problems so the need seldomly arises to compute higher order Taylor expansions (at least in machine learning where computing higher order gradients at scale can be expensive).

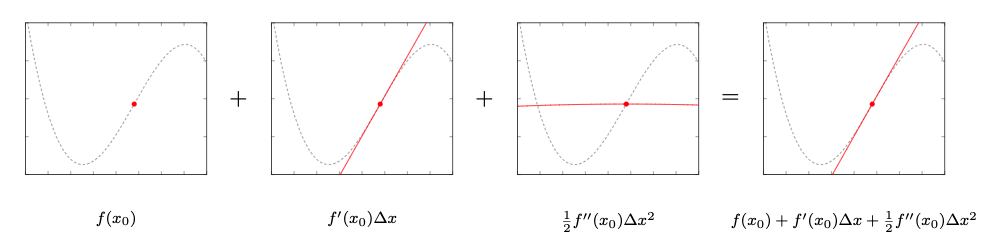

So we’ll be working with the following sum: \(\begin{align} f(x)|_{x_0} &\approx f(x_0) + \frac{f'(x_0)}{1!}(x-x_0) + \frac{f''(x_0)}{2!}(x-x_0)^2 \\ &= f(x_0) + f'(x_0) \underbrace{(x-x_0)}_{\Delta x} + \frac{1}{2!}f''(x_0) \underbrace{(x-x_0)^2}_{\Delta x^2} \\ &= f(x_0) + \underbrace{f'(x_0) \ \Delta x}_{\text{linear in $\Delta x$}} + \underbrace{\frac{1}{2}f''(x_0) \ \Delta x^2}_{\text{quadratic in $\Delta x$}} \\ \end{align}\) where $\Delta x = (x - x_0)$ signifies the distance of x to the root point $x_0$. By using the second order Taylor expansion we approximate the higher order polynomial $f(x)$ with just its first and second order derivative packed into a polynomial in $\Delta x$. The locality of the Taylor expansion around the $x_0$ is essential for the approximation since we use the first order order derivative $f’(x_0)$ and second order derivative \(f''(x_0)\) explicitly evaluated at $x_0$.

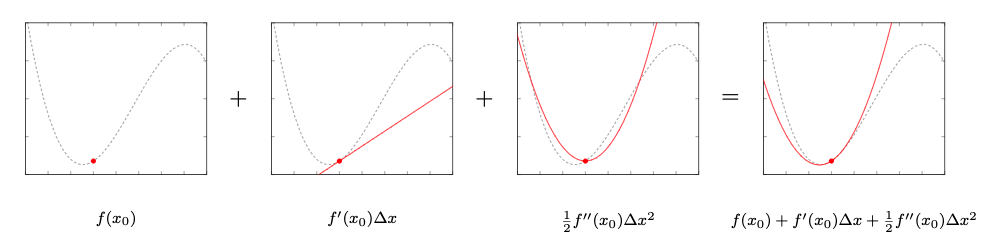

We can visually the individual points of the Taylor expansion around the root point:

We can observe a couple of things in these plots:

- The root point $x_0$ stays the same for all plots since this is the point around which we try to locally approximate the function $f(x)$ with a lower order polynomial

- The first order derivative $f’(x_0) \Delta x$ is a linear function that goes through $x_0$. I omitted the constant term $f(x_0)$ for visual clarity what the individual components contribute to the overall approximation. Strictly speaking it would need to be $f(x_0) + f’(x_0) \Delta x$.

- The second order derivative \(f''(x_0)\Delta x^2\) is a constant value which doesn’t change. The root $x_0$ lies on a stretch with almost no curvature ergo \(f''(x_0)\) is almost constant and doesn’t contribute much to the final approximation.

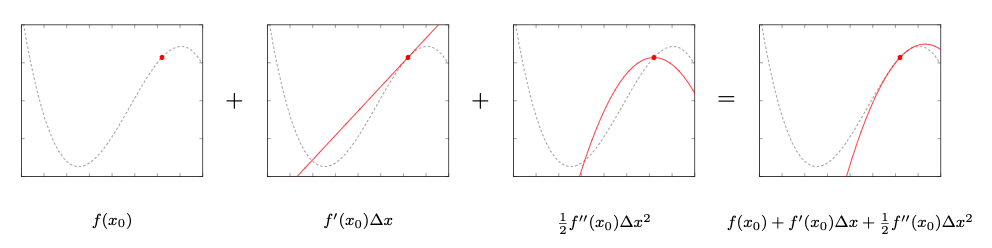

Now let’s move the root point $x_0$ and plot the different terms again to see the second order derivative \(f''(x_0)\) in action:

With this root point $x_0$ we can see the second order derivatives actually contribute to the final approximation:

- Now the root point lies in an area in which there is high curvature.

- The second order term of the Taylor approximation plays a more significant role and we can see that it tries to approximate the function around $x_0$ with a quadratic function.

- Furthermore the sum of the two terms approximate the original function around the root point more precisely than either could have done on its own.

Now the question can be raised on how this could be applied to stochastic processes …

Ito’s Lemma

Let’s assume we a classic SDE with a drift term $\mu(t, X_t)$ and a diffusion term $\sigma(t, X_t)$ which together form: \(\begin{align} dX_t = \mu(t, X_t) dt + \sigma(t, X_t) dW_t \end{align}\) and $dW_t$ is the infinitesimal differential of a Wiener process $W_t$. Such a process is commonly called an Ito drift-diffusion process.

Now let’s say that we have some function $f(t, X_t)$ that takes whatever value $X_t$ is at the moment $t$ and returns some other value $Y_t$ such that we have \(\begin{align} Y_t = f(t, X_t) \end{align}\) We could use relatively easy functions such as as the exponential function $e^{X_t}$ or the quadratic function $X_t^2$ for starters. In the financial markets, these functions $f$ quickly get very complex as stock prices are routinely modeled as stochastic differential equations with $f$ capturing complex relationships like a portfolio performance or default probability.

Since we are working with infinitesimal differentials we would like to know how $Y_t$ changes for very small time differentials $dt$. So we actually want to be able to define the following equation: \(\begin{align} dY_t = df(t, X_t) \end{align}\) In order to answer that question, Ito’s lemma applies a Taylor expansion to $f(t, X_t)$ with special numerical conditions for the infinitesimal values. There are a few constraints on $f$, though. It has to be twice differentiable with respect to $X_t$ and at least once differentiable with respect to $t$. If these equations are met we can start deriving!

The first step is to define the Taylor expansion for $f(t, X_t)$ in it’s general form around the root point $(t_0, X_0)$: \(\begin{align} f(t, X_t) &\approx f(t_0, X_0) + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} \underbrace{(t - t_0)}_{\Delta t} + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} \underbrace{ (X_t - X_0) }_{\Delta X_t} + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t}\underbrace{(X_t - X_0)^2}_{\Delta X_t^2} \\ &= f(t_0, X_0) + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t}\Delta X_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t}\Delta X_t^2 \end{align}\)

The next step is to examine the Taylor expansion in the limit $\lim [t \rightarrow t_0, X_t \rightarrow X_0]$. This is of interest as we are again interested in the infinitesimal behavior of $f(t, X_t)$, namely $df(t, X_t)$: By pulling the root evaluation $f(t_0, X_0)$ over to the left side we lay the groundwork for the differential. \(\begin{align} \lim_{t\rightarrow t_0, X_t \rightarrow X_0} f(t, X_t) - f(t_0, X_0) &= \lim_{t\rightarrow t_0, X_t \rightarrow X_0} \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t}\Delta X_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t}\Delta X_t^2 \end{align}\)

In fact the limit above is precisely the differentiability operator from the very beginning. Remember that we define the differentiability as the difference of two evaluations for an ever more decreasing difference in their arguments. This is precisely what we are defining in the limit above by moving $t$ ever closer to $t_0$ and simultaneously $X_t$ towards $X_0$. Furthermore the limit also allows us to rewrite the difference $\Delta t$ and $\Delta X_t$ in their infinitesimal differential form $dt$ and $dX_t$.

So we obtain the following: \(\begin{align} \lim_{t\rightarrow t_0, X_t \rightarrow X_0} f(t, X_t) - f(t_0, X_0) &= \lim_{t\rightarrow t_0, X_t \rightarrow X_0} \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t}\Delta X_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t}\Delta X_t^2 \\ \end{align}\)

where the left sides simplifies to the differential of the function $f$: \(\begin{align} df(t, X_t) &= \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} dX_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} dX_t^2 \end{align}\)

The next step is substituting $dX_t = \mu(t, X_t)dt + \sigma(t, X_t)dW_t$ into the equation: \(\begin{align} df(t, X_t) &= \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} dX_t+ \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} dX_t^2 \\ &= \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} (\mu(t, X_t)dt + \sigma(t, X_t)dW_t) + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} (\mu(t, X_t)dt + \sigma(t, X_t)dW_t)^2 \\ &= \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} (\mu(t, X_t)dt + \sigma(t, X_t)dW_t) \\ & \quad + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} (\mu(t, X_t)^2 dt^2 + 2 \mu(t, X_t) \sigma(t, X_t)^2 dt dW_t + \sigma(t, X_t)^2 dW_t^2) \\ \end{align}\)

Now comes a pivotal part in the derivation in which examine how $dt$ and $dW_t$ behave when multiplied or squared. The differential Wiener process can be rewritten as $dW_t = \epsilon \sqrt{dt}$. Thus we have the following time-dependent terms appearing in the equation above: $dt^2$, $dt dW_t = \epsilon dt^{1.5}$ and $dW_t^2 = \epsilon^2 dt = dt$ under the mean-square interpretation which states $\mathbb{E}[\epsilon^2] = \mathbb{V}[\epsilon] = 1$ for $\epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)$.

The important aspect of simplifying Ito’s lemma is to think about how $dt^2$, $dt^{1.5}$ and $dt$ behave for infinitesimal changes. Any $dt^k$ with $k>1$ and $dt < 1$ will decrease by an order of magnitude faster to zero than $dt$ itself for the infinitely small values that we’re dealing with. So if we evaluate for a infinitesimal small $dt$, the terms $dt^2$ and $dt^{1.5}$ will be smaller by larger order of magnitudes. This allows us to simply drop them from our equation.

So we now have: \(\begin{align} df(t, X_t) &= \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} (\mu(t, X_t)dt + \sigma(t, X_t)dW_t) \\ & \quad + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} (\mu(t, X_t)^2 \overbrace{dt^2}^{\rightarrow 0} + 2 \mu(t, X_t) \sigma(t, X_t)^2 \overbrace{dt dW_t}^{\rightarrow 0} + \sigma(t, X_t)^2 \overbrace{dW_t^2}^{=dt}) \\ &= \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} (\mu(t, X_t)dt + \sigma(t, X_t)dW_t) + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} \sigma(t, X_t)^2 dt \\ &= \underbrace{\left(\frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} \mu(t, X_t) + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} \sigma(t, X_t)^2 \right)dt}_{\text{deterministic}} + \underbrace{\frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} \sigma(t, X_t)dW_t}_{\text{stochastic}} \\ &= \mu_f\left(t, \mu(t, X_t), \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial t}, \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t}, \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} \sigma(t, X_t)^2 \right)dt + \sigma_f\left(t, \sigma(t, X_t), \frac{\partial f(t_0, X_0)}{\partial X_t} \right) dW_t \end{align}\)

So ultimately, it turns out that the derivative of the function $f(t, X)$ with an Ito drift-diffusion process as input is an Ito drift-diffusion process itself. Albeit with a few first and second order derivatives sprinkled in between.

Thus we can model the function $f(t, X_t)$ just like any other drift-diffusion process and can evaluate the distribution of such a process at a later point in time.