Gaussian Processes - Basics

A Tutorial for Gaussian Processes

Introduction

Many problems in science and engineering can be formulated as a mathematical optimization problem in which an optimal solution is sought, either locally or globally. The field of global optimization is the application of applied mathematics and numerical analysis towards finding the overall optimal solution in a set of candidate solutions. Local optimization is considered an easier problem, in which it suffices to find an optimum which is optimal with respect to its immediate vicinity. Such a local optimum is obviously a suboptimal solution and, while harder to find, global optima are more preferred.

Generally, optimization problems are formulated as finding the optimal solution which minimizes, respectively maximizes, a criterion, which is commonly referred to as the objective function. Further constraints on the the set of solutions can be formulated, such that only a subset of solutions are permissible as candidates for the optimum.

Optimization is commonly done in an iterative manner where the objective function is evaluated for multiple candidate solutions. Due to the iterative nature, it becomes desirable to evaluate this function as few times as possible over the course of the entire optimization, which becomes even more crucial when the evaluation of the objective function itself is costly. Therefore, it would be advantageous to infer information about the objective function beyond the evaluations themselves, which only provide punctual information.

Bayesian inference models provide such advantages since they compute predictive distributions instead of punctual evaluations. One class of Bayesian inference models are Gaussian processes (GP), which can be applied to model previous evaluations of the objective function as a multi-variate Gaussian distribution. Given such a Gaussian distribution over the previous evaluations, information can be inferred over all candidate solutions in the feasible set at once.

Gaussian Processes

In most situations where observations have many small independent components, their distribution tends towards the Gaussian distribution. Compared to other probability distributions, the Gaussian distribution is tractable and it’s parameters have intuitive meaning. The theory of the central limit theorem (CLT) makes the Gaussian distribution a versatile distribution which is used in numerous situations in science and engineering.

A convenient property of the Gaussian distribution for a random variable $X$ is its complete characterization by its mean \(\mu\) and variance $\Sigma$:

\[\begin{align} \mu &= \mathbb{E}[X] \\ \Sigma &= \mathbb{E}[(X-\mu)^T(X-\mu)] \end{align}\]Mathematically, a multivariate Gaussian for a vector $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ is defined by its mean $\mu \in \mathbb{R}^d$ and covariance function $\Sigma \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d}$:

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{N}(x | \mu, \Sigma) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{(2 \pi)^d |\Sigma|^2}} \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} (x-\mu)^T \Sigma^{-1}(x-\mu) \right] \\ &\propto \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} (x-\mu)^T \Sigma^{-1}(x-\mu) \right] \end{align}\]A useful property of the Gaussian distribution is that its shape is determined by its mean and covariance in the exponential term. This allows us to omitt the normalization constant and determine the relevant mean and covariance terms from the exponential term.

Let $y=f(x)$, where $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ and $y \in \mathbb{R}$ be the function which we want to estimate with a Gaussian Process. Furthermore, let $\mathcal{D} = (X, y) = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=0}^N$ with $X \in$ $\mathbb{R}^{N \times d}$ and $y \in \mathbb{R}^{N}$, be our training observations of the function $f$.

Lastly, let $ \mathcal{D}_* = ( X_* , y_* ) = \{ ( X_{ * j } , y_{ * j } ) \} _{j=0}^{ N_* } $ with $ X_* \in \mathbb{R}^{N_* \times d} $ and $ y_* \in \mathbb{R}^{ N_* } $ , be the test observations at which we want to compute the predictive distributions of $ y_* =f( X_* ) $ for the function $ f $.

A Gaussian process is defined as a stochastic process, such that every finite collection of realizations $ X = \{ x_i \}_{ i=0 }^N , x_i \in \mathbb{R}^d$ of the random variables $ X \sim \mathcal{N}( \cdot | \mu, \Sigma), X \in \mathbb{R}^d $ is a multivariate distribution.

A constraint of Gaussian processes as they are used in machine learning, which can be relaxed in specific cases, is that they are assumed to have a zero mean. In order to compute a predictive distribution over $ y_* $ we initially construct the joint distribution over the training observations $\mathcal{D} = (X,y) $ and test observations $ \mathcal{D}_* = ( X_* ,y_* ) $:

\[\begin{align} p(y_*, y, X_* , X) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{(2 \pi)^{ N+N_* } |K|^2}} \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \begin{bmatrix} y \\ y_* \end{bmatrix}^T \begin{bmatrix} K_{ XX } & K_{ X X_* } \\ K_{ X_* X } & K_{ X_* X_* } \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} y \\ y_* \end{bmatrix} \right] \\ &\propto \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \begin{bmatrix} y \\ y_* \end{bmatrix}^T \begin{bmatrix} K_{ X X } & K_{ X X_* } \\ K_{ X_* X} & K_{ X_* X_*} \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} y \\ y_* \end{bmatrix} \right] \\ &\propto \mathcal{N} \left( \begin{bmatrix} y \\ y_* \end{bmatrix} \middle| \mathbf{0}, K \right) \end{align}\]where the covariance matrix of the joint Gaussian distribution is given by

\[\begin{align} K=\begin{bmatrix} K_{ X X} & K_{ X X_* } \\ K_{ X_* X} & K_{ X_* X_* } \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} k( X, X) & k( X, X_*) \\ k(X_*, X) & k(X_*, X_*) \end{bmatrix} \end{align}\]and $ k(x,x’) $ is an kernel function $ k: \mathcal{X} \times \mathcal{X} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ that measures the similarity between two vectors $ x, x’ \in \mathcal{X}$. We can observe from \eqref{eq:covariance1} that the covariance between any two observations in the distribution is determined by the similarity through the kernel function $k(x, x’)$, namely

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{C}[y, y'] = k(x, x') \end{align}\]An essential component of a GP is the kernel function with which the covariances is computed. Often the kernels are engineered to incorporate prior knowledge. A commonly used kernel is the squared exponential kernel

\[\begin{align} k(x, x' \ ; \ \theta) = \alpha \exp \left[ - \frac{|| x - x'||^2}{2 \sigma^2}\right], \quad \theta = \{ \alpha, \sigma \} \end{align}\]where $\theta$ corresponds to the hyperparameters of the Gaussian process which can be independently optimized with respect to the observations $(X, y)$.

Gaussian Processes can be readily extended to multiple dimensions by simply adjusting the kernel to incorporate multiple dimensions. The individual variances $\sigma_i$ of the dimensions $\mathbb{R}^d$ in the exponential kernel can be independently adjusted, or optimized with the maximization of the marginal probability of the data. The expanded kernel for multidimensional input is defined as followed:

\[\begin{align} k(x, x'; \ \theta) &= \alpha \exp \left[ - \frac{1}{2} (x-x') \Sigma^{-1} (x-x') \right], \quad \theta=\{ \alpha, \Sigma \} \\ \Sigma &= \text{diag}(\sigma^2_0, \sigma^2_1, \ldots, \sigma^2_d) \end{align}\]The block matrices $k(X,X) \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}$ $ k(X, X_* ) \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N_* }, $ $k( X_* , X ) \in \mathbb{R}^{ N_* \times N }$ and $k(X_* , X_* ) \in \mathbb{R}^{N_* \times N_* }$ are the Gramian matrices of the training and test observations with respect to the kernel $k(x, x’)$.

Furthermore both $k(X,X)$ and $k( X_* , X_* )$ are symmetric matrices and $k( X, X_* )$ and $k( X_* ,X)$ are each others mutually transposed.

Given the joint distribution $ p(y_* , y, X_* , X) $, the aim for modeling the training and test observations with a GP is to derive the posterior distribution $ p( y_* | y, X_* , X ) $ . In order to derive the mean and covariance function of the posterior distribution, the block matrix inversion lemma is used to compute the inverse of the covariance matrix.

For ease of reading and brevity the respective block matrices were replaced by more easily readible variables in the following identity:

\[\begin{align} K^{-1}&= \begin{bmatrix} K_{ X X} & K_{ X X_* } \\ K_{ X_* X} & K_{X_* X_* } \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \label{eq:blockmatrixinversionlemma1} \\ & =\begin{bmatrix} A & B \\ C & D \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \\ &=\begin{bmatrix} A^{-1} + A^{-1}B(D-CA^{-1}B)^{-1}CA^{-1} & -A^{-1}B(D-CA^{-1}B)^{-1} \\ -(D-CA^{-1}B)^{-1}CA^{-1} & (D-CA^{-1}B)^{-1} \end{bmatrix} \\ &=\begin{bmatrix} A^{-1} + A^{-1}B\Sigma^{-1}CA^{-1} & -A^{-1}B\Sigma^{-1} \\ -\Sigma^{-1}CA^{-1} & \Sigma^{-1} \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:Sigma^-1Identity} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} P & Q \\ R & S \end{bmatrix} \label{eq:blockmatrixinversionlemma-1} \\ \Sigma &= D-CA^{-1}B = K_{X_* X_* } - K_{ X_* X}{K_{ X_* X_* }}^{-1}K_{X X_* } \end{align}\]Instead of computing the inverse of the entire matrix $K$, which can be computationally expensive for large covariance matrices, the precision matrix $K^{-1}$ can be computed block-wise with the block matrix inversion lemma. Given the precision matrix in block matrix notation, the inner product in the exponential term of the Gaussian distribution can be computed as a sum over the inner products with the independent block matrices:

\[\begin{align} p(y_* , y, X_* , X) &\propto \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \begin{bmatrix} y \\ y_* \end{bmatrix}^T \begin{bmatrix} K_{XX} & K_{X X_* } \\ K_{X_* X} & K_{X_* X_* } \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} y \\ y_* \end{bmatrix} \right] \\ &= \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \begin{bmatrix} y \\ y_* \end{bmatrix}^T \begin{bmatrix} P & Q \\ R & S \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} y \\ y_* \end{bmatrix} \right] \\ &= \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \left( y^TPy + y^TQ y_* + y_*^TRy + y_* ^TS y_* \right) \right] \label{eq:jointdist_innersumoverblockmatrices} \end{align}\]Since we are only interested in the posterior distribution $p(y_* | y, X_* , X )$, terms which do not include $ y_* $ can be moved into the normalization term. The conditional distribution can thus be simplified to:

\[\begin{align} p(y_* | y, X_* , X) &\propto \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \left( -y^TQy_* - y_*^TRy + y_*^TS y_* \right) \right] \\ &= \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \left( -y^TA^{-1}B\Sigma^{-1} y_* -y_*^T\Sigma^{-1}CA^{-1}y + y_*^T\Sigma^{-1}y_* \right) \right] \\ &\propto \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \left( -2 y_*^T\Sigma^{-1}CA^{-1}y + y_*^T\Sigma^{-1}y_* \right) \right] \\ &\propto \exp \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \left( -2 y_*^T\Sigma^{-1}K_{X_* X}{K_{ X X }}^{-1} y + y_*^T\Sigma^{-1}y_* \right) \right] \end{align}\]with the matrices $\Sigma$ being a symmetric matrix by construction, and $B$ and $C$ being each other transposed, namely $C^T=B$, which gives rise to the identity: \(\begin{align} (y^TA^{-1}B\Sigma^{-1}y_*)^T &= y_*^T(\Sigma^{-1})^TB^T(A^{-1})^Ty \\ &= y_*^T\Sigma^{-1}CA^{-1}y \end{align}\)

Alternatively one would argue that the result of both inner products yields the same scalar value due to $B=C^T$. With the derivations above we obtain a posterior distribution $p(y_* | y, X_* , X )$ with the mean and covariance function

\[\begin{align} \mu(y_*) &= K_{ X_* X}{K_{XX}}^{-1}y \\ \Sigma(y_*) &= K_{ X_* X_* } - K_{ X_* X}{K_{ X X }}^{-1}K_{ X X_*} \end{align}\]It should be noted that during plotting only the diagonal entries of the covariance matrix are of interest since the diagonal entries of the covariance matrix denote the variances at the evaluated points. Given the computation of both the mean and variance of the posterior distribution we obtain a Gaussian distribution: \(\begin{align} p(y_* | y, X_*, X) &= \mathcal{N} \big( \underbrace{K_{X_* X} {K_{XX}}^{-1} y}_{\mu}, \underbrace{K_{X_* X_*} - K_{X_* X}{K_{X X}}^{-1}K_{X X_*}}_{\Sigma} \big) \end{align}\)

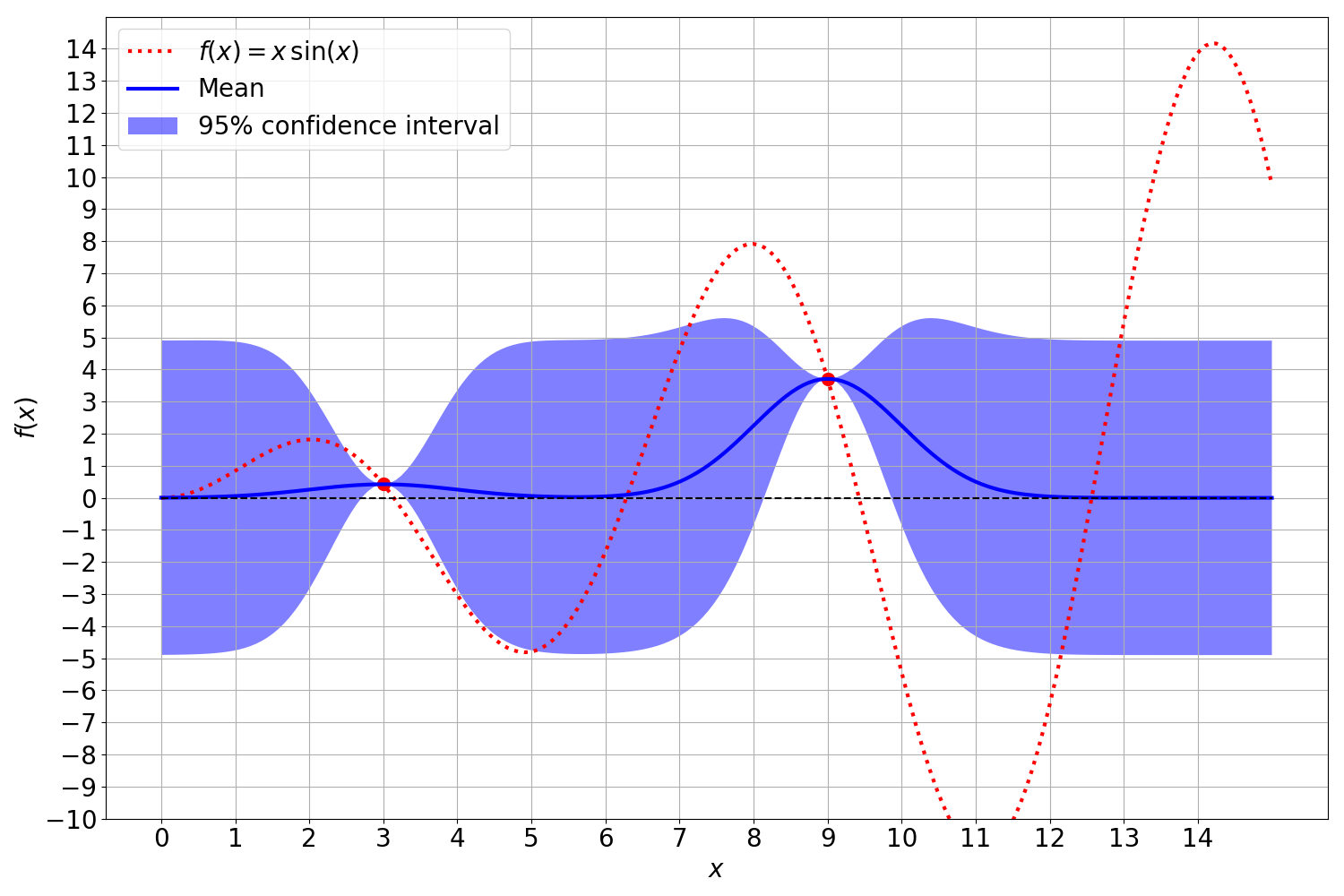

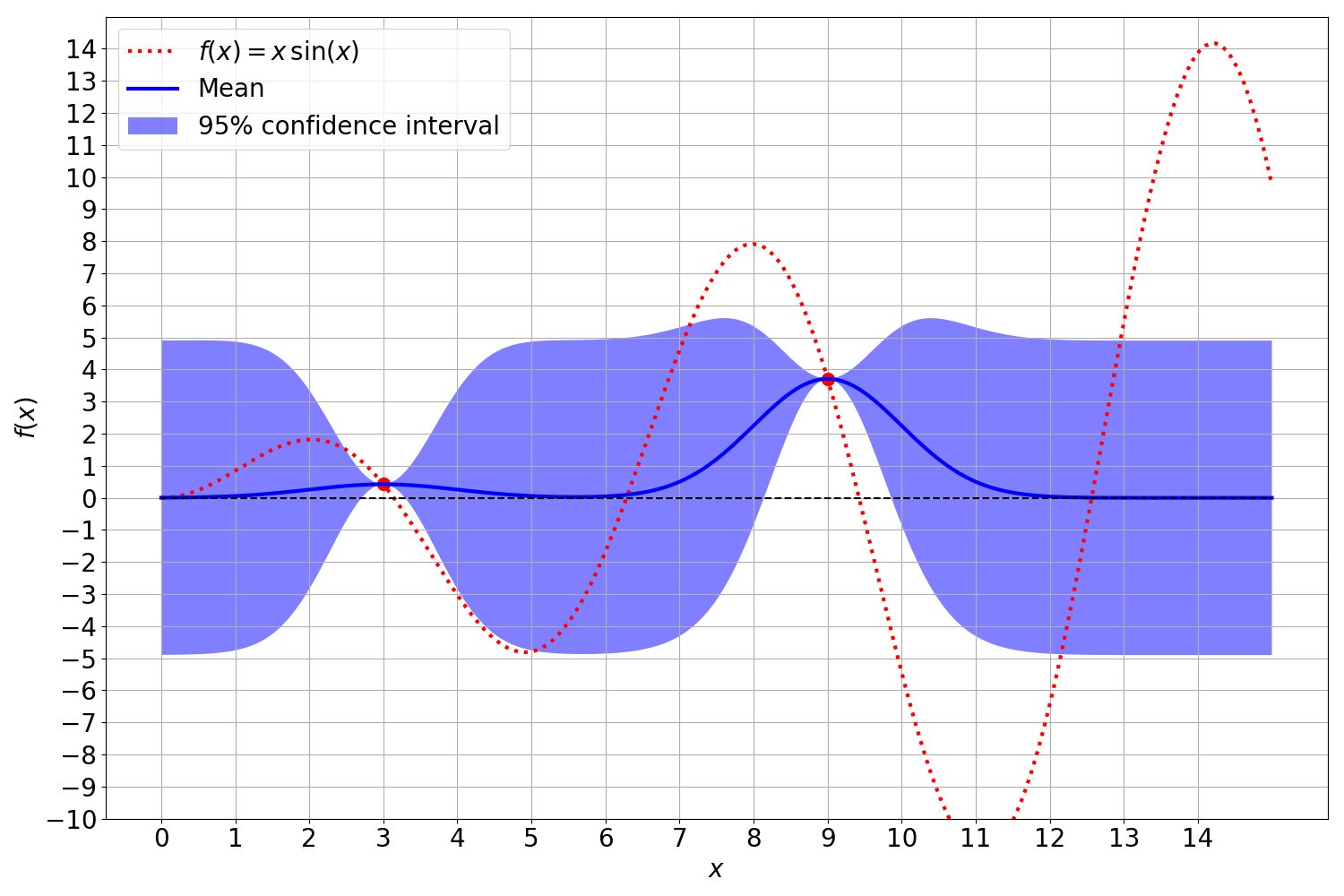

Here is an image of a Gaussian Process: