The Adjoint Method in Neural Ordinary Differential Equations

Reverse-Mode Sensitivity Training

The Adjoint Method in Neural Ordinary Differential Equations

Back at NeurIPS 2018 the best paper award was given to the authors of Neural Ordinary Differential Equations.

The motivation of the paper was the mainly given through the interpretation of the ResNet architectures being interpreted as the Euler discretization of ordinary differential equations (ODE). The paper took this insight to its logical extreme and asked the question whether we really have to remain content with just the Euler discretization of an ODE or whether we can go deeper … or more continuous in our case.

By definition an ODE is defined in its differential form as \(\begin{align} dz_t = f(z_t, t, \theta) \end{align}\) which basically means that the function $f$ computes the rate of change of $z_t$ at timestep $t$ with its parameters $\theta$. Often these equations $f$ are constructed analytically or are known from physics but a more interesting question cane be posed by asking whether this function $f$ can actually be learned … with a neural network for example.

Ultimately, if we want to use gradient based optimization to train a neural network we need to compute a scalar loss function and compute the gradients of the parameters $\theta$ through reverse-mode autodifferentiation.

An important part of solving/simulating differential equations is that although they are defined in the continuous space, we have to discretize eventually in order to make the problem amenable to a solution with computers.

For that reason we will work with four samples ${z_0, z_1, z_2, z_3 }$ from a differential equation as shown in the image below. Our prediction with a neural network will be denoted as ${\hat{z}_1, \hat{z}_2, \hat{z}_3 }$.

Working with neural networks, we want to obtain gradients which which we can perform gradient descent at the end of the day. In order to do that we will need a scalar cost function on which we can perform reverse-mode autodifferentiation which is very efficient for models with potentially a lot of parameters. If the model were to be very small we could also do forward-mode autodifferentiation but that’s another topic.

Let’s define such a scalar cost function $\mathcal{L}(\text{ODESolver}(z_0, t_0, t_3, f))$ that takes in $z_0$ and solves the ODE for four timesteps by integrating forward $f(z_t, t, \theta)$ in time until it reaches $t=3$ and compares the prediction with the true values ${z_0, z_1, z_2, z_3 }$.

Now comes the interesting part: How do we actually compute the gradients with respect to the parameters, namely $\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \theta}$?

The thing is that the parameters $\theta$ occur at multiple timesteps in the prediction. The key insight is now that we actually have to ask ourselves two questions: “How much did each timestep contribute to the loss?” and “At each timestep how much did each parameter contribute to the loss?”.

Enter adjoint sensitivity analysis …

The first question can be answered by examining the sensitivity of the scalar loss with respect to the different timesteps $\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_t}$.

The sensitivity $\frac{\partial L}{\partial z_3}$ of the loss with respect to the last timestep can be readily evaluated. More interesting is how we could propagate the sensitivity backwards in time to all evaluated timesteps. The solution to this problem is the use of the Jacobian of the output $z_t$ with respect to the input $z_{t-1}$: \(\begin{align} J(f)= \frac{\partial f(z, t, \theta)}{\partial z} = \left[ \begin{array}{cccc} \frac{\partial f(z, t, \theta)_1}{\partial z_1} & \dots & \frac{\partial f(z, t, \theta)_D}{\partial z_1} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial f(z, t, \theta)_1}{\partial z_D} & \dots & \frac{\partial f(z, t, \theta)_D}{\partial z_D} \\ \end{array} \right] \end{align}\) The Jacobian of the function $f$ with respect to the input tells us how sensitive the output is to the input. Since the solution of the ODE is theoretically an infinite series of evaluations of the neural network $f$ we can similarly backpropagate the initial sensitivity $\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_t}$ by repeatedly multiplying it with the Jacobian with respect to the input but backward in time, which is an ODE again but this time it’s backwards. Said differently, we simply reweight the initial sensitivity repeatedly with the Jacobian backwards through time.

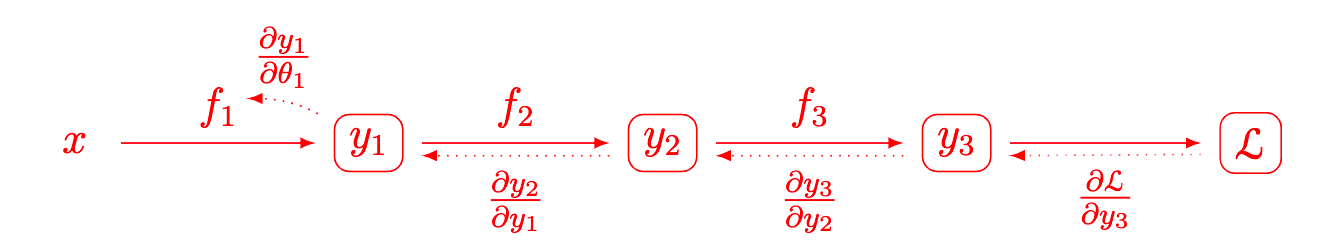

The sensitivity backward pass for our discretized ODE problem would then look something akin to this: \(\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_1} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_3} \frac{\partial f(z_2, t, \theta)}{\partial z_2} \frac{\partial f(z_1 t, \theta)}{\partial z_1} \end{align}\) This procedure is actually very similar to how the normal backpropagation pass is done. In a neural network we use the chain rule to first compute the gradients for the last layer, and then repeatedly reweight the gradients as they are passed through the network. Take a three layer network as an example with $y = f_3(f_2(f_1(x, \theta_1), \theta_2), \theta_3)$.

Computing the gradients for $\theta_1$ from the loss amounts to little more than: \(\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \theta_1} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial y_3} \frac{\partial y_3}{\partial y_2} \frac{\partial y_2}{\partial y_1} \frac{\partial y_1}{\partial \theta_1} \end{align}\) This is what the authors in the paper refer to as “… which can be thought of as an instantaneous analog of the chain rule.”. In essence, the adjoint sensitivity pass allows us to propagate the importance of each timestep to the overall loss backwards through time.

Once we propagated the sensitivity backwards through time, we can answer the second question by computing the gradient of the output with respect to the parameter in question.

While the authors of the paper use the term adjoint state $a(t)$ I find the term sensitivity $s(t)$ more intuitive and appealing. The beauty of the adjoint state training became apparent to me when I used sensitivity $s(t)$ in equation (5): \(\begin{align} \frac{\partial L}{\partial \theta} = \int_{t_1}^{t_0} s(t)^T \frac{\partial f(z(t), t, \theta)}{\partial \theta} dt \end{align}\) The integral above states that we scale the gradient of the output $\partial_\theta f(z(t), t, \theta)$ with the sensitivity $s(t)$ to the overall loss.

Interestingly, the reception by the differential equation community was not as unanimous as one would think as this method has been used for a fairly long time. The key insight was its application to neural networks since we only need the Jacobians of the neural network irrespective of what goes on inside the neural network. One of the coauthors said as much in a talk a year later.